In November, the United Kingdom together with their partner Italy, will host an event many believe to be the world’s last best chance to get runaway climate change under control. The UN, for the past three decades has been bringing together almost all countries for global climate summits – called the COPs – which stands for ‘Conference of the Parties’. During this time, climate change turned from a fringe issue to a global priority. The question has to be asked, what went wrong?

Scene 1: Genesis

Our story begins in 2015, when Paris Agreement came into existence during the 21st Conference of the Parties held in Paris. For the first time, a landmark decision to combat climate change was taken. Every country agreed to work together to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees and aim for 1.5 degrees, compared to pre-industrial levels, to adapt to the impacts of a changing climate and to make money available to deliver on these aims.

Under the Paris Agreement, countries agreed to bring forward national plans setting out how much they would reduce their emissions – known as Nationally Determined Contributions, or ‘NDCs’. They committed that every five years they would come back with an updated plan which would reflect their highest possible ambition at that time. The run-up to this year’s COP which is to be held in Glasgow, is the time for countries to update their plans for reducing emissions. This however, now faces a setback. The commitments laid out in Paris did not come close to limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees. What makes this worse is the window for accomplishing the laid targets is closing. If we do not stop this from derailing, we may just be looking at a 2.7 degree rise by the end of this century.

UN Climate Change on the 17th of September published a synthesis of climate action plans as communicated in countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The NDC Synthesis report indicates that while there is a clear trend that greenhouse gas emissions are being reduced over time, nations must urgently redouble their climate efforts if they are to prevent global temperature increases beyond the Paris Agreement’s goal.

Scene 2: Carbon space

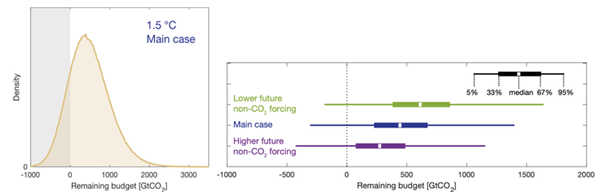

One may define the carbon space as the amount of carbon (or CO2) that can be put into the atmosphere without it leading to a level of warming or underlying concentrations of CO2 that would be considered dangerous or otherwise undesirable. Every nation has their own carbon space which they may exploit over a period of time. The consensus at the moment is that the total carbon space available to mankind is 1,000 gigatons of CO2. We began consuming this space around the year 1850, with the onset of industrialisation. Since then we (mostly developed countries) have exhausted almost 600 gigatons of CO2. This leaves us with a remaining buffer of only 400. At our current rate of emissions, we would emit the 1,000th gigaton around the year 2035. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that limiting global average temperature increases to 1.5C requires a reduction of CO2 emissions of 45% in 2030 or a 25% reduction by 2030 to limit warming to 2C.

Because the developed countries used up most of the carbon space while industrialising themselves, the now developing countries do not have enough share left for themselves. Up to 20% of the global carbon space is still being used by China and 16% by the US. This therefore poses huge challenges in front of the developing nations because they now have the added pressure of emitting lesser carbon while trying to develop themselves. Most such countries unfortunately, do not have the technical know-how or enough money to execute such plans formed by their developed counterparts at the UN. The UN therefore decided to mobilise finance for such nations. The developed countries must now deliver on their promise to raise at least $100bn in climate finance per year. International financial institutions should also play their part in order to work towards unleashing the trillions in private and public sector finance required to secure the net zero target. This however, does not look too good as of now. The commitment of mobilizing funds which was made in the UNFCCC process more than 10 years ago has not yet been fulfilled. It’s time to deliver, and as many hope, COP26 is in fact the place to do so.

Scene 3: Common but Differentiated Responsibilities

Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC) is a principle within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that acknowledges the different capabilities and differing responsibilities of individual countries in addressing climate change, since all countries are not equally developed, equally rich or equal contributors towards climate change.

On the 27th of August, The BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) released a New Delhi Statement on Environment at the 7th meeting of BRICS environment ministers. It emphasised the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities. The statement said BRICS countries will cooperate closely ahead of the critical UN climate change negotiations (COP 26) and emphasised that developed countries will have to honour their financial commitment of USD 100 billion per year to developing countries for climate change mitigation.

“We agree to cooperate closely in the run up to the 26th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC COP26) in the United Kingdom and the 15th meeting of the Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP15) in China. We took note of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group 1 contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report and noted that it is a clarion call for rapid, sustained and effective science-based responses to climate change,” the statement said.

The union environment minister of India, Mr. Bhupender Yadav who chaired the meeting stated that India gives great importance to BRICS; “2021 is a very crucial year not only for the BRICS but for the whole world as well, as we have UN Biodiversity COP 15 in October and UNFCCC COP 26 in November. BRICS Countries can play a very significant role in addressing the contemporary global challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, air pollution, marine plastic litter etc.”

Scene 4: India at COP26

With less than a week for the COP26 to commence, India finalises its preparation ahead of the 26th Conference of the Parties to be held in Glasgow. India, which is the third largest emitter of carbon dioxide on the planet, has not agreed to the net zero deadline.

4.1. India rejects the net zero target

India sees the mid-century target as opposite to the principle of CBDR-RC. This net zero target means that the country must commit to a year beyond which its emissions won’t peak and a point at which it will balance out its emissions by taking out an equivalent amount of greenhouse gas from the air (hence, net zero.)

The practicality of this target however, is open for a debate. To even theoretically commit to such a target by 2050 would require India to shut all its 400 thermal power plants down and stop all its dependence on fossil fuels overnight. This unachievable target gets worse because we can still not be too sure if doing this will prevent the temperature rise to stay below the 1.5 degree target by the end of this century!

India at the same time avers that most of the countries clamouring for a net zero target for India will continue, even with their national stated reduction targets, to pollute on a per capita basis way beyond their fair share. India adds that countries responsible for the climate crisis haven’t fulfilled their previous promises to fund mitigation and adaptation projects and so the future net zero promises are therefore hollow.

4.2. Expectations

India welcomed the UK COP26 Presidency’s five key initiatives on sustainable land use, energy transition, low emission vehicle transition, climate finance and adaptation. India was also hoping to strengthen global climate initiatives including the International Solar Alliance, Coalition Disaster Resilient Infrastructure (CDRI), leadership Group for Industry Transition (LeadIT Group), Call for Action on Adaptation and Resilience and Mission Innovation. The COP26 should also be initiating the process of setting the long-term climate finance for the post-2025 period. The summit therefore involves arriving at a consensus on unresolved issues of the Paris Agreement Rule Book, long-term climate finance and market-based mechanisms.

4.3. Demands

India shall remain “open to all options” as long as commitments made in the previous COPs are met. These commitments include developing countries getting compensated to the tune of $100 billion annually, the carbon-credit markets be reinvigorated and the countries historically responsible for the climate crisis be compensated by way of “Loss and Damages,” and clean development technologies be made available in ways that its industries can painlessly adapt to.

Scene 5: Too little, too late?

“Weak promises, not yet delivered”

Just days before the COP26 climate summit, UN’s Environment Programme (UNEP) released a statement on the 26th of October stating that national plans to reduce carbon pollution amounted to “weak promises, not yet delivered.” The onus to mitigate the climate crisis thus lies in the hands of G20 nations, who are in fact responsible for 78% of all emissions. Although the developed nations have the responsibility to step up and set more optimistic targets, eventually all 193 member states of the UN will have to take initiative.

The world now finds itself in damage control mode. Reports by the IPCC show that the ship to undo the effects of anthropogenic harm done towards the environment has sailed already. The best we can do now is to limit the damage as much as possible. While one may call this a thundering wake up call, the question has to be asked, how many wake up calls do we need? Scientists have been warning us about climate change for decades now. Unfortunately however, humans sacrificed the only planet known to harbour life to its capitalist needs. The emissions gap is the result of a leadership gap, something that should’ve been worked on decades ago. The era of half measures and hollow promises must now end. The time for closing the leadership gap must begin in Glasgow.

A report by the UNEP mentioned that the plans of many of the 49 countries that have made “net-zero” pledges remained “vague” and were not reflected in their formal commitments. The only people we are lying to, are ourselves. While everyone looks at Glasgow with hope, one must acknowledge that the time is now to fulfil the promises made previously, and the ones which are yet to be made at the COP. With eight years in hand to form policies and implement them, we now need to deliver the timely cuts to minimise the mess we are about to bring ourselves into.

As years of COP negotiations have shown, progress is glacial and the effort is more on delivering a headline announcement rather than genuine operationalisation of the steps that need to be taken. In real terms, for developed countries, complying with the demand by developing countries to pay reparations means shelling out sums of money unlikely to pass domestic political muster. And for developing countries, yielding to calls for ‘net zero’ means that governments such as India will appear as having caved into international bullying.

Conclusion: The silver lining

Glasgow, if taken seriously, holds a lot of potential to change the world. COP26 is the first step after the Paris Agreement to diagnose and rectify the plans we proposed back in 2015. The world can join hands and move towards a better future. A future for all the generations to come. The best gift we can ever give to the following generations, is a planet which continues to harbour life as we know it. India should introduce equity in the net zero targets or at least present it as a proposal for discussion. It needs to go beyond the $100-billion demand and focus on tangible deliverables. For the power, mobility and hydrogen sectors, India may only need $12-15 billion per annum which should be given at 4% interest rate subvention. And lastly, India should focus on the development of technology, how to reduce the cost of technology for mitigation and co-development of technology. There should also be progress on Article 6 (that deals with the carbon trading markets). While it may all seem hard at first, we must remind ourselves, humans have achieved unimaginable and extraordinary feats before and we certainly can do it now. All it requires is for the policy makers, politicians, youth and the children of this planet to walk hand in hand towards a better tomorrow.

“There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

-Carl Sagan (1994, Pale Blue Dot)

Leave a comment