On the 24th day of February 2022, the world was taken by surprise. The orders came in from Moscow and a full-fledged invasion of Ukraine was underway. An invasion of such intensity was not anticipated by any other government elsewhere, reasoning that it would be logistically impossible to occupy the territory and that the local resistance would be prolonged and potentially ruinous to the invading forces. Soon, the rest of the world found itself quickly imposing sanctions and trade embargoes. The UNGA overwhelmingly condemned the Russian Federation and demanded the immediate withdrawal of troops. It was not long before calls for boycotts to supplement the sanctions began to pour in. The scientific community, for its part, did not back down from proposing such boycotts as well. This, however, wasn’t the first time the calls for boycotts echoed throughout the scientific community.

Scene 1: The First Boycott

Although the practice of punishing perceived wrongdoing by withholding trade or succour has existed since time immemorial, it was not given a permanent label until 1880. It happened when the local community of County Mayo, Ireland shunned the overbearing land agent for Lord Erne. The case became so severe that, to reap the harvest, workers had to be imported from distant countries and guarded. With that Pyrrhic victory, Charles Boycott left Ireland on December 1, 1880. Those who were outraged by the powerful’s impunity never forgot him, and the end of the century was littered with boycotts of various kinds. The scientific world quickly joined in.

Before Moscow however, the scientific boycotts were focused on Berlin. The most significant — so much so that its legacy still colours, often unconsciously, all later discussions of the practice — was that imposed in 1919 by the French, Belgian, British and US scientists on the vanquished powers of the Great War. Or, more accurately, it was imposed on the successor states of the vanquished; the democratic republic of Weimar Germany and the new states of Austria and Hungary.

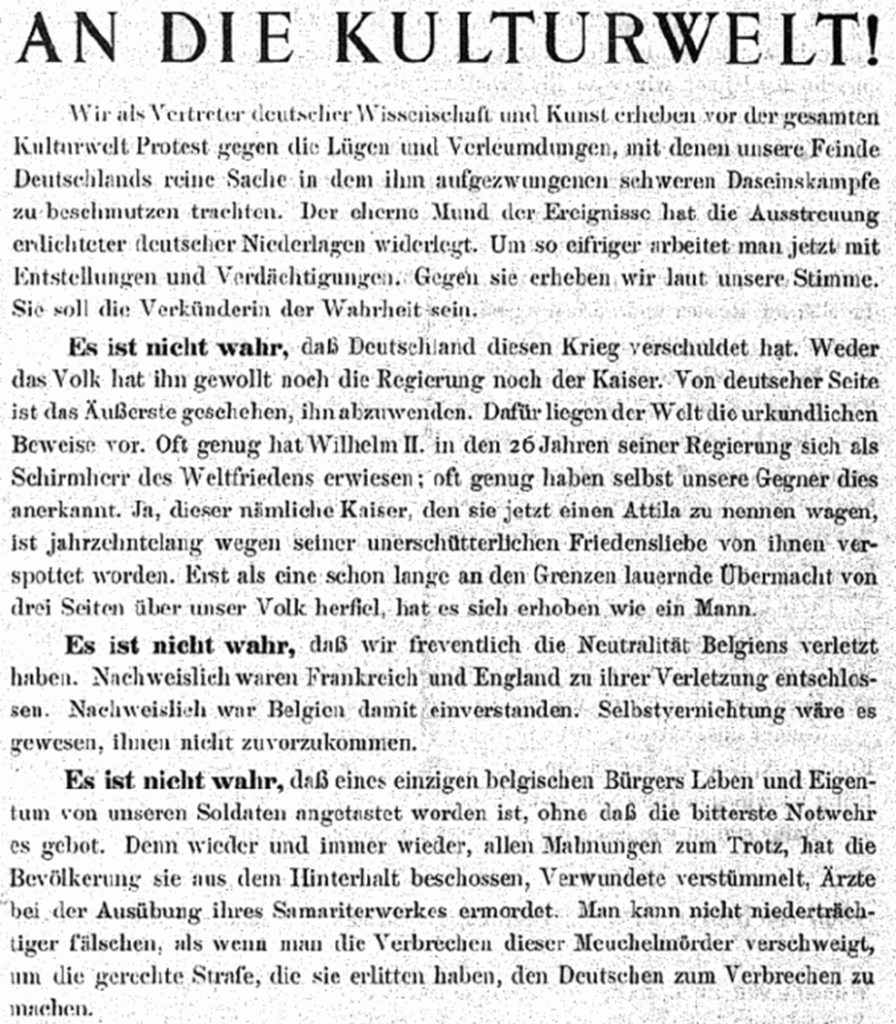

Many specific transgressions were invoked as justifications for punishing all scientists from the losing nations. The most frequently cited incitement was the notorious Manifesto of the Ninety-Three, a proclamation officially entitled ‘To the Cultured World’ that was signed by a host of literary and philosophical luminaries and released on 4 October 1914. The document aimed to defend the honour of Germany against the allegations of atrocities committed by the German troops during the invasion of Belgium. The list of prominent signatories on the document was what irritated the later boycotting scientists. Scientists like Adolf von Baeyer, Paul Ehrlich, Fritz Haber, Felix Klein, Walther Nernst, Wilhelm Ostwald, Max Planck and Wilhelm Röntgen were among the signatories.

Unfortunately, however, these scientists who were willing to politicise the quest for knowledge were repaid in their coin. After the war ended, all scientists from the losing nations including the signatories were excluded from conferences and scientific meetings, denied space in journals published by the boycotting powers and barred from participating in the new administrative structures of international science that were being restructured on the ruins of pre-war transnational organisations. It was planned that the boycott would last until 1931.

Scene 2: Einstein’s Great Escape & Evanescent Peace

One exception, who wasn’t caught in the crossfire between Germany and the rest, was Albert Einstein. He was recognized as one of the four signatories to an anti-war counter-manifesto, To the Europeans, penned by Einstein’s Berlin colleague and like-minded pacifist, the physiologist Georg Nicolai. Despite the ban on German nationals, Einstein was feted in 1919 when the successful results of a British expedition to test the general theory of relativity during a solar eclipse were announced. In no time, Einstein found himself travelling to the boycotting United States and France in 1921 and 1922 respectively. He did have his conditions though: for one, he only entertained invitations that were addressed specifically to him but refused to go to any international meeting, such as the Solvay conferences in physics in 1921 and 1924, as those denied access to Germans. He firmly believed that the boycott was terrible for science, and so did those countries that had remained politically neutral during the conflict, such as the Netherlands and Denmark. Their scientists contended that blanket condemnation was utterly pointless and ineffective. Ironically, the strictures granted sites such as physicist Niels Bohr’s institute in Copenhagen outsized importance as places of rendezvous between the boycotters and the boycottees.

Not like Austrian and German scientific communities desperately needed the rest of the world either. They were vibrant and diverse enough to function reasonably well without being in contact with the shunning nations. Thus the boycott was believed to be absolutely toothless and incomplete. The neutral scientists constantly argued that the only thing that was being hurt by the boycott, was science, and so they lobbied hard for the League of Nations to accept the now-democratic Germany to its ranks, signalling the end to the scientific boycott. And so the boycott finally came to an end, five years before it was intended to, in 1926. Among other things, Einstein attended the Solvay conference the following year.

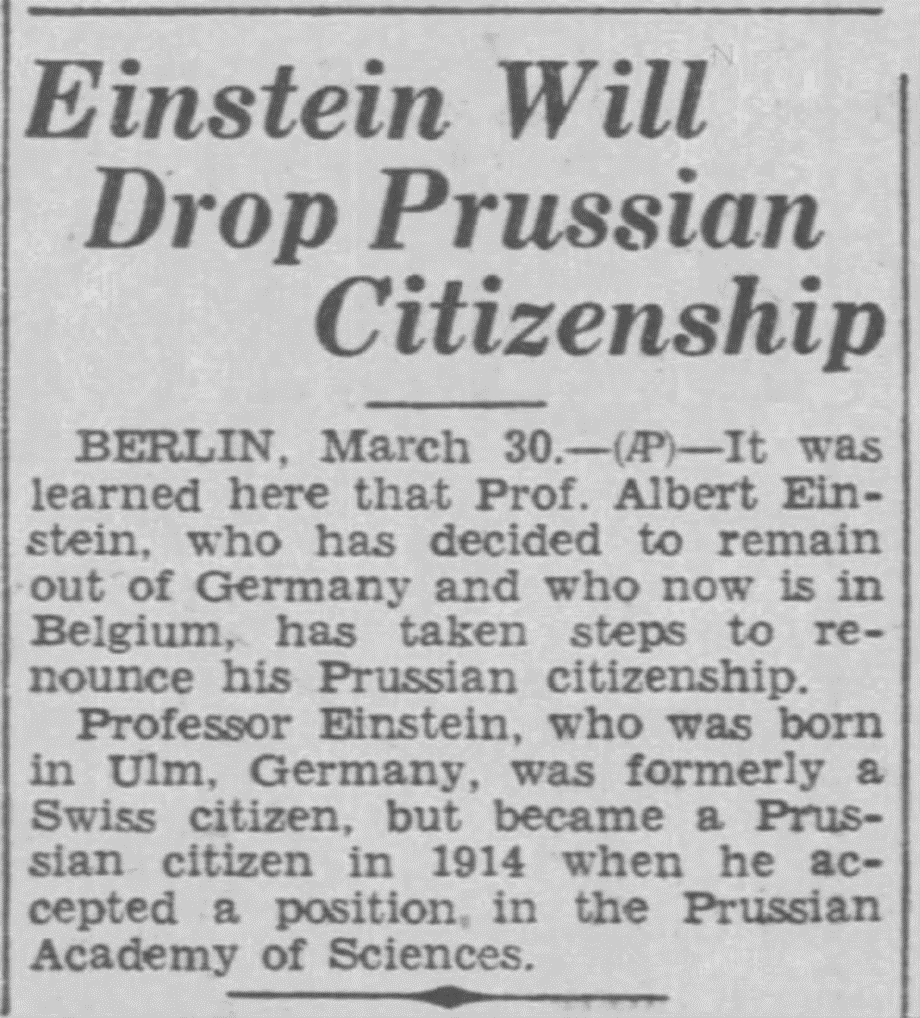

It wasn’t long until the calls for boycotts returned. The appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, and his complete seizure of power a few months later, a Civil Service Law fired the vast majority of Jewish people, including scientists, from university positions. This time, however, Einstein sided with the boycotters, as he openly resigned from his position at the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin in March 1933, frustrating the state’s attempts to publicly fire him. He also refused to publish in German journals. “The German intellectuals have as a whole behaved disgracefully concerning all the abominable injustices and have richly deserved to be boycotted,” he wrote to his exiled colleague Cornelius Lanczos from Princeton University in New Jersey in 1935. Similarly, in 1939, physicist Percy Bridgman of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, announced that he would no longer share information with former colleagues in “totalitarian states,” referring to Germany. Hitler’s regime, for its part, boycotted the journal Nature when it persisted in calling attention to Nazi crimes.

The Second World War soon cut off connections between Germany and its antagonists, but on the grounds of military secrecy rather than morality. Following the war, scientists from the Allied nations spearheaded efforts to reintegrate former belligerents.

Scene 3: A Stamping Ground for Russia

The boycott remained a favoured tactic, but a failed gambit, since it had not demonstrably accomplished any change in behaviour in its previous deployments. The Cold War found its advocates among the scientists who wanted to boycott the Soviet Union to protest against the subjugation of Eastern Europe. But how could they? For the first decade after the Second World War, there wasn’t too much left for the capitalist nations to boycott. Thus, the Berlin Blockade of 1948–49 and the suppression of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956 were greeted only with private indignation by scientists. The idea of boycotts didn’t remain farfetched for long. Within a decade of Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviet and especially US scientists launched a concerted campaign to integrate the former into emerging global scientific networks. As a means of easing tensions, the Lacy-Zarubin Agreement of 1958 established exchanges between the United States and the Soviet Union in a variety of artistic and scientific fields. With the deepening of détente in the early 1970s, such exchanges accelerated.

President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger were more concerned with arms control and geopolitical leverage than with scientific communication. Their efforts in the former, however, resulted in advancements in the latter, including a series of exchanges between the US National Academy of Sciences and the Soviet Academy of Sciences. So, because of this trend of rapprochement, the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, was only able to produce faint calls for a boycott.

It was going well for Russia until the Soviet-Afghan war broke out. The US was under the impression that a boycott will force the Soviets to fall back, after all, those efforts at integration were regarded as valuable, and something the Soviet leadership would be reluctant to lose. However, to the surprise of the Americans, it had no effect on the Soviet deployment, which lasted until 1989. Even before that, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s wave of glasnost and perestroika reforms had catalysed an even more vigorous effort to integrate Soviet scientists into global science. A similar push occurred with post-Soviet scientists after 1991. The financial and intellectual investment that resulted was the polar opposite of a boycott. Philanthropic support was provided by financier George Soros’ International Science Foundation in Moscow and New York City, as well as the MacArthur Foundation in Chicago, Illinois; US state support was provided through the Civilian Research and Development Foundation in Arlington, Virginia; and multilateral collaboration was facilitated by the International Science and Technology Center in Moscow and its Kyiv counterpart, the Science & Technology Center in Ukraine, among others. The investments forged new links between the scientific communities of the former Soviet Union’s successor states and international science.

The catch? All of this effort was being expended on a rapidly shrinking scientific community of the fallen soviet states. The scientific workforce in these regions dropped by at least 50%, partly because of scientists emigrating to other countries but mostly because of the lack of funding for laboratories and better-paid jobs in the private sector. The quantity of investment and the associated uptake by scientists remained modest even after the economic crisis of the 1990s and after the governments of Putin and Dmitry Medvedev raised budgetary allotments. Though it was a shadow of the Soviet size, what was left was more closely related to trans-national science.

Scene 4: Is a Scientific Boycott Ever Justified?

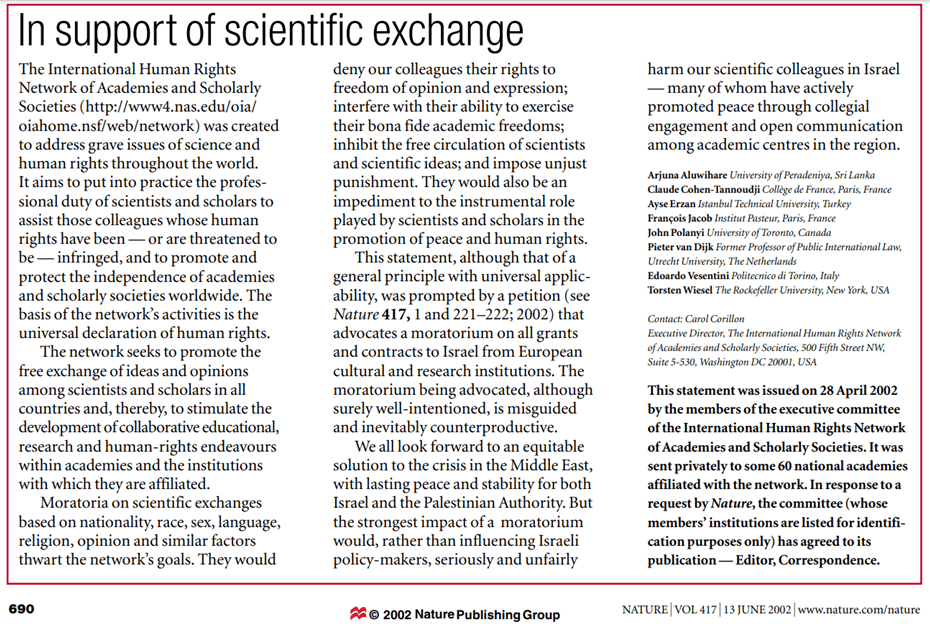

One thing that has, through the years, kept science going is its universality. This universality of science seeks to prevent scientists’ use as pawns in political activity. Science has found itself being caught in the crossfire of differences in political interests from time to time, leading to boycotts. It is not widely known that such discrimination is explicitly forbidden by the International Council for Science (ICSU) as contrary to the principle of ‘universality of science.’ The ICSU includes nearly 100 national academies of science and research councils and 26 international scientific unions. In order to address grave issues of science and human rights around the globe, the International Human Rights Network of Academies and Scholarly Societies was also established. It aims to put into practice the ethical responsibility of scientists and academics to support their peers whose human rights have been violated or are in danger of doing so, as well as to advance and defend the independence of academies and scholarly societies around the world. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights serves as the framework for the network’s operations. In order to encourage the growth of cooperative educational, research, and human-rights endeavours inside academies and the institutions with which they are affiliated, the network aims to foster a free exchange of ideas and opinions among scientists and intellectuals in all countries.

ICSU’s fifth statute describes the universality of science as follows: “This principle entails freedom of association and expression, access to information, and freedom of communication and movement in connection with international scientific activities without any discrimination on the basis of such factors as citizenship, religion, creed, political stance, ethnic origin, race, colour, language, age or sex.” Although some scientists argue that this statement contains a few imperfections, its prohibition against discrimination on the grounds of citizenship is clear and unambiguous.

But it is clear that the universality of science cannot be a tenet of absolute inviolability. As an extreme case, imagine that the only option to prevent nuclear war was to declare a global boycott of diplomatic, trade, and cultural ties with a rogue regime. Wouldn’t the majority of scientists concur that a boycott would be appropriate?

So, could there be less extreme situations where it would be OK to discriminate or engage in a boycott of scientists? The value of a scientific discovery is independent of the characteristics of the discoverer, and the continued ability of scientists to collaborate and transcend boundaries is an important symbol of and impetus for the dissolution of political divisions. These points must all be taken into account when responding to this question. The free communication of information and ideas has historically been significant in the liberalization of autocratic regimes — for example, it was a factor leading to the end of totalitarian regimes in Eastern Europe. Authoritarian governments try to suppress the flow of information and ideas and control the participation of their citizens in international activities. The task of scientists in other countries is surely not to exclude their colleagues who live under such regimes from international contacts, but rather to draw them into dialogue.

Scene 5: The Ukraine Crisis and the Boycott of Russia

Regardless of the Ukrainian scientific community urging other national science academies and journals to boycott Russian scientists, (or more specifically, the scientists who work in Russia) the response has been passive. At the moment, the Journal of Molecular Structure, produced by publishing giant Elsevier, is the only journal reported to be boycotting manuscripts from Russia.

According to Caroline Sutton, CEO of the trade association International Association for Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers (STM), no publishers that she is aware of have decided to prohibit publishing papers of Russian researchers, “A few are discussing that inside.” She adds. Her group doesn’t make any collective decisions. Anyone having to think about this predicament is aware of its gravity, she continues. Science editor-in-chief Holden Thorp insists there will be no boycott.

The impact on the total quantity of scientific articles would be minimal even if many journals joined the boycott. In 2018, roughly 82,000 papers were published with contributions from Russian authors, which is only about 3 percent of the total worldwide and the second-lowest among 15 major nations. However, in comparison, their share had increased quickly: according to the U.S. National Science Foundation, Russian papers had climbed by 10% yearly over the previous decade, more than those of any other major nation outside India. This growth is in part due to a decision made by the Russian government in 2012 to award academics for the number of articles they publish.

Despite the expansion, Russia’s annual production of papers has remained well below that of the Soviet Union, which was a larger nation and spent a larger proportion of its GDP on science, when it split up in 1991. Peer review of Russian articles has also lagged. According to STM, they received the fewest citations in 2019 out of papers from 10 major nations. As per Michael Gordin, a historian at Princeton University who has researched Russian science, one explanation is that many scientists publish in Russian-language publications. According to him, the lack of Russian scientists participating in international collaborations, partly due to U.S. restrictions on their ability to visit, is another factor contributing to the low number of citations.

However, scientific ties between the West and Russia aren’t limited to scientific journals and published papers. On February 25, 2022, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) notified the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology (Skoltech) (Moscow, Russia) that it was exercising its right to terminate the MIT Skoltech Program “in light of the unacceptable military actions against Ukraine by the Russian government.”

The countries that abstained from boycotting Russia were China, India and South Africa. One of the reasons why these countries want to maintain links with Russia is the fact that these countries are members of the BRICS; the others being Brazil and Russia. This group works together to promote trade and economic development and has an active programme of scientific cooperation. Vaccines are an important focus along with biodiversity, climate and food security. Not only these nations but the Islamabad-based organisation Comstech representing science ministers from countries that are part of the 57-member Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), is also discussing a long-term science-cooperation agreement with Russia, which is an observer state to the OIC.

China has found itself playing an East-West balancing act claiming that it maintains a “neutral stance” on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Universities, research organizations and funding agencies are not making public statements, but there are no signs that collaborations will be affected. Over the last decade, there has been a steady increase in research publications with authors from the two countries, however, this is consistent with China’s research expansion along with many more countries. Physical sciences, particularly physics and astronomy, as well as materials science and engineering, stand out as prominent subjects for Chinese and Russian scholars. China and Russia designated 2020–21 as a year of scientific and technological innovation, with plans for collaborations in nuclear energy, COVID-19 research and mathematics, among other fields. Since certain Russian banks have been restricted from using the international financial-transactions infrastructure SWIFT, transfers between Russia and China are likely to be made in the currencies of the two countries. China has also launched an alternative to SWIFT called the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System.

Amongst all this, the Modi-Putin science plan has emerged as a new favourite for both states. India has had less scientific interaction with Russia during the last few decades than with Europe and the United States. However, in December 2021, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed to boost bilateral scientific ties. The leaders agreed on a lengthy list of topics on which they want to see more cooperation. Agriculture and food science and technology, ocean economy, climate, data science, energy, health and medicine, polar research, quantum technologies, and water are among them. This would be in addition to existing ties in nuclear energy and space. Russia has supplied India with nuclear reactors and fuel, and the countries’ space cooperation dates back to the 1970s. In 1984, Rakesh Sharma, an Indian Airforce pilot, joined the Soviet Union’s Soyuz T-11 expedition, becoming the first person from India to travel to space. Some observers and stakeholders believe that this decision of strengthening ties with Russia will eventually have a more serious impact on India’s research collaborations across the board. Trade sanctions against Russia may prevent scholars in India and Russia from exchanging research materials. Furthermore, banking sanctions will most certainly prevent capital from being transferred through overseas banks. To get around this, India and Russia are said to be talking about dealing in rupees and roubles rather than US dollars.

Conclusion: Administrators vs Academics

In a recent open letter, more than 200 rectors of Russian universities expressed unconditional support for Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine. The letter shocked many Western scholars. The European University Association suspended the membership of universities that signed the letter, and the breaking of academic ties with Russia increased. The consequence of breaking these relationships, however, is clear: any sanctions placed on Russian academics are likely to harm the more liberal faction while boosting their more conservative opponents. What this means is that severing ties with Russian universities will do the opposite of what’s intended, and strengthen Putin’s isolationist supporters.

The political stances of high-level administrators at Russian universities are not representative of the academic community. Indeed, the divide between scholars and administrators is much wider than in most European countries. Since the 1990s, the conservative and liberal camps have been competing for sway over Russian science and research policy. Until recently, the liberal group had – paradoxically – greater support from the Russian government. The reasons were twofold. First, Russian state bureaucrats suspected the older, more conservative establishment of being inefficient or simply corrupt based on numerous reports of misconduct ranging from plagiarism to the sale of fraudulent degrees. Second, the liberal camp was able to supply something that their opponents could not. The Russian state considers science (together with athletics and art) as a source of international prestige and a tool of soft power, and it is acutely aware of how its academics compare to those of other countries.

In recent years, the authorities’ primary goal has been to elevate Russian institutions to the top of worldwide rankings. This necessitates substantial publication in foreign publications. Because the isolationist academic camp is isolated from the global intellectual landscape, the bureaucrats were forced to turn to their liberal opponents, no matter how unpalatable their political beliefs were. However, Western sanctions are currently undermining these liberals. QS and Times Higher Education (THE), two of the three most important university rankings providers, have announced that they will no longer work with Russian institutions – thus giving the conservative side a nearly unbeatable argument as to why these rankings should be ignored. After Clarivate, the owner of a major citation index, said it will stop including new Russian and Belarusian journals, the Russian government announced that indexed papers will no longer be regarded as a performance target.

Similarly, ceasing ties with foreign institutions harms the stature of international-minded Russian intellectuals. Breaking academic ties with Russia is likely to tip the balance of power in favour of the conservative wing, consolidating control over universities and research institutes while silencing liberal opponents. This is clearly the opposite of what was intended.

The academic boycotts may appear to some to be no different than conventional economic sanctions. After all, why should scientific interactions be treated any differently from Champions League soccer matches, Formula One Grand Prix, ballet performances, commercial transactions, and investment projects, all of which have been cancelled in recent days? The truth is, there are various reasons to differentiate. One is that there is more to be lost by severing intellectual links. A cancelled Bolshoi ballet performance will cause no long-term harm to the globe. Breaking up scholarly collaboration, on the other hand, will hamper research on pressing issues such as climate change, in which Russian scholarship plays a significant role, particularly on the warming Arctic. It will also increase the risk of war. This price might be worth paying if it would tip Russian domestic opinion against the war. But far from strengthening Russian doves, the academic boycott will undercut them.

Tragically, at the end of the Cold War, the West squandered the opportunity to forge a lasting peace. Today, it is once again confronted with a hostile Russian state. Western institutions that want to make a genuine contribution to conflict resolution should remember how and why the Cold War ended. Even now, the majority of Russians see their country as a victim of unjustified Western hostility, rather than as an aggressor. It is critical in this setting to keep channels open to Russian journalists and researchers. This is not to condone aggression, but it does provide the possibility of finally persuading Russians that their country is on the wrong course.

Leave a comment