When we think of climate change, carbon often takes centre stage. It is no surprise given its direct and visible impact on global warming. But what if I told you that another element, nitrogen, contributes to climate change and leads to environmental pollution, yet it remains largely overlooked? In the words of Mark Sutton, an environmental physicist and an expert on nitrogen –

“The tricky thing about nitrogen as opposed to carbon, is that it is literally everywhere, doing all sorts of things. It’s like the godfather of pollution: you see the results, but you don’t see the godfather.”

Neglecting nitrogen can undermine our efforts to create a sustainable future. This blog post aims to shed light on nitrogen’s significant yet underappreciated role in contributing to climate change, water pollution, air quality, and biodiversity loss. Despite its sporadic presence in policy discussions, public awareness about nitrogen pollution remains alarmingly low. By illuminating the profound impacts of nitrogen, we hope to spark a broader conversation on the urgent need for sustainable nitrogen management.

Scene 1: Beyond Carbon: The Environmental Consequences of Nitrogen Pollution

Nitrogen, which makes up nearly 78 per cent of Earth’s atmosphere, is predominantly found in its chemically inert and environmentally harmless gaseous form (N2). It is also a crucial building block of life. However, to sustain life, nitrogen must be “fixed” — a process that involves breaking the triple bond between two nitrogen atoms to create chemically reactive nitrogen species (Nr). Most living organisms cannot perform this process of biological nitrogen fixation — the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3). However, a few specialised organisms known as diazotrophs carry out this essential process, initiating the nitrogen cycle and supporting the survival of life.

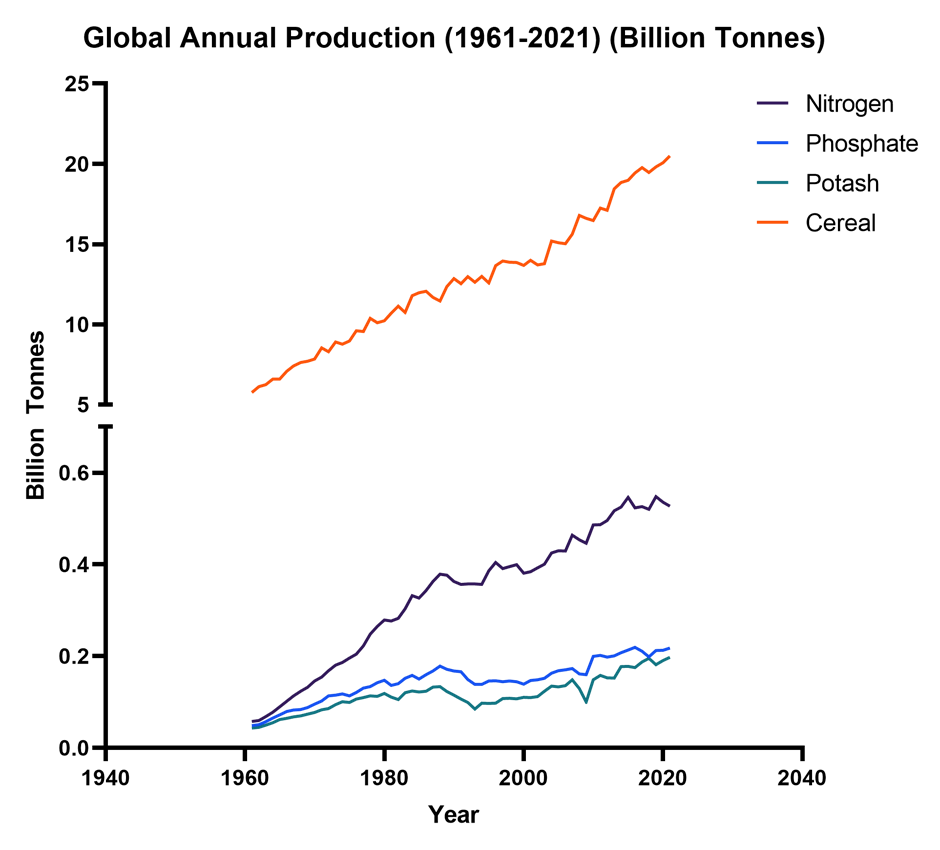

Throughout geological history, the nitrogen cycle was relatively balanced, with natural processes like lightning and nitrogen-fixing bacteria controlling the availability of reactive nitrogen – until the advent of the Haber-Bosch process during the early 20th century. This process, which also synthesises ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen, became the primary method for producing synthetic nitrogen fertilisers, which has been essential in supporting the Green Revolution by dramatically boosting global food production (Figure 1), contributing to feeding about half the current global population (Raghuram et al., 2022).

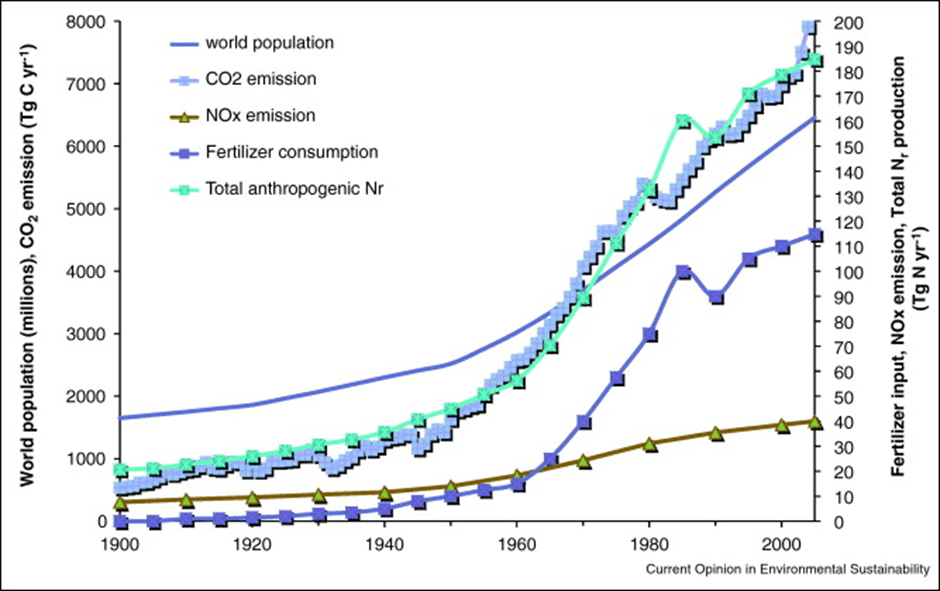

Figure 2 illustrates the rise in anthropogenic reactive nitrogen species over the past century. This increase correlates strongly with the Green Revolution and the global shift towards intensive agricultural practices. This has led to the anthropogenic disruption of the global nitrogen cycle (Wang et al., 2021, UNECE, 2021). More than half of the reactive nitrogen species (nitrates, nitrogen oxides (NOx), ammonia, urea and other amine derivatives etc.) currently found in the environment can be attributed to anthropogenic origin (Fowler et al., 2013).

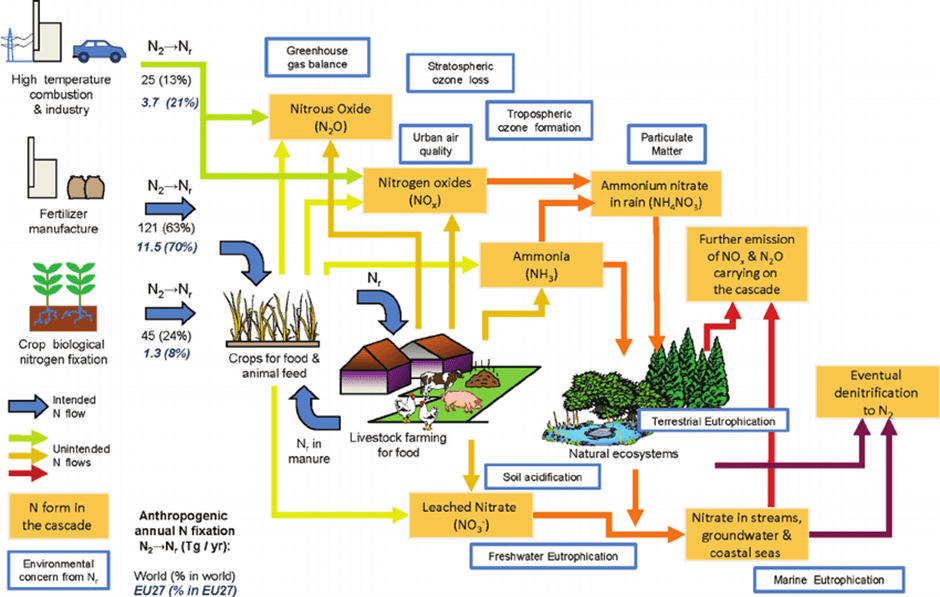

The anthropogenic conversion of atmospheric nitrogen to reactive nitrogen species spans multiple sectors (UNEP, 2019). Transportation and fossil fuel-based energy generation account for 13% of the total conversion of atmospheric nitrogen into reactive nitrogen species. The excessive use of nitrogenous fertilisers in intensive agriculture is the most significant source of nitrogen pollution, contributing a staggering 63% of anthropogenic reactive nitrogen. In contrast, biological nitrogen fixation contributes only 24%. Additionally, poor management of waste such as sewage, wastewater, and food contributes to non-point reactive nitrogen pollution (UNEP, 2019).

Nitrogen pollution poses a significant threat to the environment, affecting water, land, and air quality, and biodiversity. The excessive loading of air and water with reactive nitrogen species has pushed us beyond the planetary boundaries for their assimilation, exceeding sustainable levels by a factor of four — our current levels should be only 25% of what they are today (Rockström et al., 2009; UNEP, 2013; Richardson et al., 2023). Close to 50% of the nitrogen input as fertiliser for agriculture is leached into the environment as pollution or is converted back to atmospheric nitrogen (UNEP, 2019).

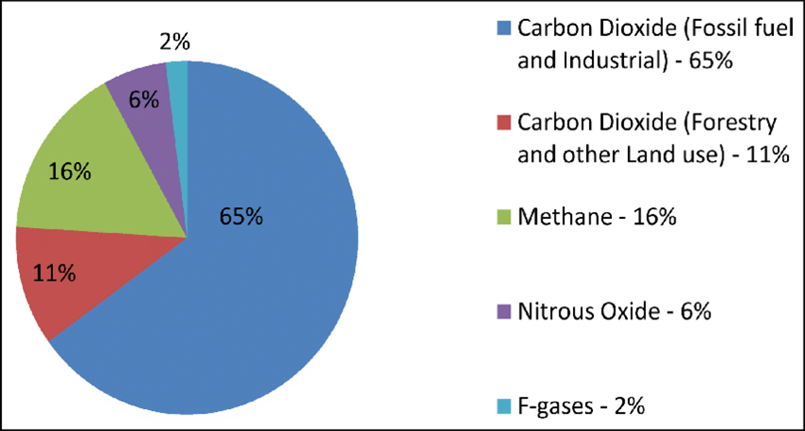

The reactive nitrogen species not utilised by plants and present in soils due to excessive fertiliser application leads to the formation of nitrous oxide (N2O) – a potent greenhouse gas with a warming potential of 300-fold that of CO2 and is also a contributor to stratospheric ozone depletion (Portmann et al., 2012, Tian et al., 2020).

The contribution of nitrous oxide amongst the Kyoto basket of six greenhouse gases (GHGs) covered under UNFCCC is given in Figure 3.

Alterations to the global nitrogen cycle have significant impacts on human health that extend far beyond the benefits associated with increased food production (Townsend et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 4, agricultural productivity reaches a plateau after a certain threshold of nitrogenous fertiliser use. However, excessive application of these fertilisers leads to an exponential increase in air and water pollution, adversely affecting public health. This results in a sharp decline in the net public health benefits, emphasising the need for balanced and sustainable fertiliser use. Nitrogen oxides (NOx) and ammonia (NH3) contribute to air pollution and pose significant health risks, including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (World Health Organization, 2018).

One of the most evident effects of reactive nitrogen pollution in water bodies is their eutrophication, caused by unused nitrogen fertiliser leaching into waterways as nitrates. This process, known as an algal bloom, depletes oxygen in the water, creating hypoxic conditions or “dead zones” where aquatic life cannot survive. Eutrophication of water bodies is a global phenomenon, to such an extent that it is difficult to find an oligotrophic water body across the globe, except high-altitude lakes. A prominent example of widespread eutrophication is the Gulf of Mexico, where nutrient runoff has created one of the largest dead zones in the world, affecting marine life and local fisheries (NOAA, 2021). Nutrient loading in aquatic ecosystems can lead to the decline of sensitive species and the proliferation of more tolerant, often invasive, species (European Nitrogen Assessment, 2011).

Nitrogen pollution also disrupts terrestrial ecosystems, leading to a loss of biodiversity. Elevated nitrogen levels can alter soil chemistry and favour the growth of nitrogen-loving plant species over others, thus reducing plant diversity. This, in turn, affects the animals that rely on these plants for food and habitat. According to Luo et al. (2022), excessive nitrogen loading in terrestrial ecosystems exacerbates phosphorus limitation and disrupts soil carbon cycling. The authors explain that increased nitrogen input enhances plant biomass production, leading to the generation of plant litter with a high nitrogen-to-phosphorus (N:P) ratio. This imbalance ultimately results in phosphorus limitation within the soil.

Scene 2: Why Nitrogen Pollution is often Overlooked

Omnipresent yet Invisible

The impacts of nitrogen pollution are both clear and profound. However, the direct linkage between these effects and excessive nitrogen use is often obscured by the complex interplay of biotic and abiotic factors. Consequently, these impacts are frequently overlooked and underappreciated, even by experts. Unlike carbon dioxide, which has been directly correlated with global warming and rising sea levels, the impacts of nitrogen pollution have not been widely appreciated, thus, leading to a lack of awareness and action by the general public.

Nitrogen pollution from agriculture and industries is not immediately apparent as other forms of pollution like plastic waste or smog. Excessive release of nitrogen in the environment is not recognised as pollution because nitrogen compounds such as nitrates are essential for life, making it difficult to distinguish between beneficial and harmful levels.

Figure 6 illustrates the nitrogen cascade, highlighting the multiple sources and pathways through which reactive nitrogen species are released into the environment via air, water, and soil.

Unlike other pollutants originating from point sources, reactive nitrogen species primarily come from non-point sources, especially in the agricultural sector. The absence of a distinct point source makes the immediate impact of such diffuse pollution less visible in its vicinity. However, the widespread nature of nitrogen pollution has profound ecosystem-wide effects on both terrestrial and aquatic environments. The gradual eutrophication of water bodies, for instance, can take years to manifest, and by then, the damage may be extensive. This slow progression allows the problem to accumulate unnoticed until it reaches critical levels.

Unlike carbon dioxide, which has a clear and well-known link to global warming and climate change, the environmental impacts of nitrogen are more subtle and dispersed. Due to the prevalence of non-point sources, the connection between nitrogen emissions and their effects is not straightforward. This complexity makes it challenging to communicate the urgency of reducing nitrogen emissions to the public. While the message to reduce fossil fuel emissions is simple and direct, the multifaceted and less visible consequences of nitrogen pollution complicate efforts to raise public awareness and drive action.

Climate change or deforestation, have been subjects of extensive media coverage and activism due to clear unambiguous communication. However, nitrogen pollution has not captured the public’s attention to the same extent. This lack of awareness means less pressure on policymakers and stakeholders to address the issue. Thus, the impacts of nitrogen pollution remain underappreciated despite its significant environmental and health impacts.

Consequently, a general lack of public awareness leads to further worsening of nitrogen pollution without any action to reduce the release of reactive nitrogen in the environment.

Inadequate Policy Response: Food Production vs Nitrogen Pollution

The practice of intensive agriculture for food production is a global phenomenon. The strong link between fertiliser use and increased agricultural productivity per unit area is considered the holy grail of farming. However, this focus has led to inadequate policy responses to nitrogen pollution from intensive agriculture.

Further, addressing nitrogen pollution requires coordinated action across different sectors and policy domains, which can be challenging to achieve. Nitrogen pollution, particularly from agriculture is still not regulated adequately across the globe. Agriculture, as the largest contributor to nitrogen pollution, creates a significant trade-off between food security and environmental health. This perceived necessity of nitrogen use often leads to a reluctance to critically assess the environmental costs associated with it. As noted by Townsend et al. (2003), the benefits of nitrogen fertilisers in feeding the world’s growing population are often misplaced beyond a threshold where the environmental impacts become more significant than the increase in agricultural productivity.

Despite numerous agricultural policies worldwide, an astounding two-thirds incentivise nitrogen use, such as through fertiliser subsidies, prioritising food production over environmental sustainability (Kanter et al., 2020). Navigating this tradeoff is inherently complex, requiring amendments to existing pro-nitrogen policies rather than creating new anti-nitrogen regulations. Achieving a balance necessitates integrating sustainable practices within current frameworks to ensure both food security and environmental preservation.

Nitrogen pollution is a multi-sectoral problem, with several stakeholders present within the agri-food system, industry, and energy production. As a result, responsibility is diffused across many sectors and individuals, making it difficult to attribute blame or responsibility, and consequently, to take action. This fragmented nature of environmental policy, coupled with competing priorities, often results in nitrogen pollution being sidelined.

Scene 3: Sustainable Nitrogen Management

Addressing nitrogen pollution requires an interdisciplinary strategy for sustainable nitrogen management. This necessitates the involvement of all stakeholders within the nitrogen cascade, from agricultural producers and industrial sectors to policymakers and scientists. Raghuram et al. (2022), have emphasised the importance of sustainable nitrogen management in agriculture. Effective nitrogen management must operate on multiple levels, from broad sectoral policies to localised, in-situ interventions. Only through such a coordinated, multi-faceted approach can the challenges of nitrogen pollution be effectively mitigated, ensuring both environmental sustainability and economic viability.

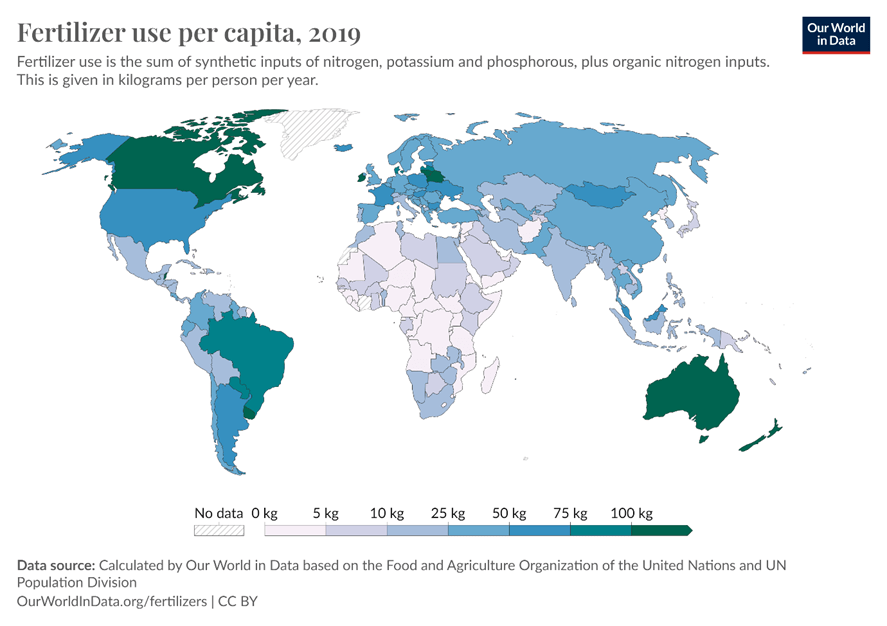

The importance of sustainable nitrogen management in agriculture need not be overemphasised, keeping in view the global practice of intensive agriculture. The developed countries are already using very high levels of fertiliser in agriculture while developing countries are also increasing their fertiliser consumption starting from a low baseline consumption (Figure 7). Figure 7 shows the per capita fertiliser consumption for the year 2019. This makes it evident that any move towards sustainable nitrogen management needs requires consolidated global effort.

| Country | 1961 | 2019 | Absolute Change | Relative Change |

| Australia | 73.14 kg | 108.32 kg | +35.18 kg | 48% |

| Brazil | 12.06 kg | 85.90 kg | +73.84 kg | 613% |

| Canada | 35.18 kg | 115.51 kg | +80.33 kg | 228% |

| China | 3.50 kg | 35.67 kg | +32.17 kg | 919% |

| Denmark | 137.39 kg | 85.35 kg | -52.04 kg | -38% |

| France | 75.38 kg | 59.34 kg | -16.04 kg | -21% |

| Germany | 58.58 kg | 33.04 kg | -25.54 kg | -44% |

| India | 3.70 kg | 22.88 kg | +19.18 kg | 518% |

| Netherlands | 57.75 kg | 32.20 kg | -25.55 kg | -44% |

| New Zealand | 141.35 kg | 206.01 kg | +64.66 kg | 46% |

| United Arab Emirates | 0.17 kg | 3.54 kg | +3.37 kg | 2004% |

| United States | 52.57 kg | 68.08 kg | +15.51 kg | 30% |

This comparative table on per capita fertiliser consumption across different countries highlights that developing nations began with a lower baseline. Both developed and developing countries demonstrate an upward trend, except the European Union member states, which have shown a decline.

Agriculture has complex socio-economic linkages. Farmers’ choice between intensive and sustainable agriculture is influenced by a range of factors, including socio-economic considerations such as input costs and return on investment, crop type, agronomic practices, and the availability of agricultural extension services. These external pressures shape farming practices and decisions, highlighting the need for systemic changes to support sustainable agriculture. Therefore, the onus shifts onto the agri-food systems’ non-farmer stakeholders to help mitigate the detrimental effects of reactive nitrogen on the environment.

One approach is to replace input-intensive practices with currently available sustainable agricultural practices. Some available options include using controlled-release fertilisers designed to release nitrogen gradually over time, matching the nutrient uptake needs of crops more closely than conventional fertilisers. This reduces the excessive reactive nitrogen burden by preventing leaching and runoff. Studies have shown that controlled-release fertilisers can significantly decrease nitrogen losses while maintaining or even enhancing crop yields (Chen, 2018).

The Government of India has made it mandatory for all urea sold in the country to be neem coated, which is projected to save 10,000 crore rupees by lowering its usage. Other similar technologies such as sulphur-coated urea and nano-urea are also being promoted by the Indian government to help decrease nitrogen losses. The Government of India is also promoting the use of the Soil Health Card in determining the rate of fertiliser application based on the status of soil fertility.

Less than 20% of input nitrogen ends up in our food, with the remainder lost to the environment (Galloway et al., 2008). Agribiotechnology offers promising solutions to enhance crops’ nitrogen use efficiency (NUE), which is crucial for reducing the level of reactive nitrogen entering the environment. By selectively breeding or genetically modifying nitrogen-inefficient crops such as rice, for high NUE traits, we can significantly reduce agricultural nitrogen pollution and its environmental impacts. Since rice feeds over half the world’s population, improving its NUE ensures that more input nitrogen contributes directly to food production rather than being lost to the environment. A shift in agronomic practices, including using controlled-release urea, combined with high-NUE crop species, will further help reduce nitrogen pollution from agriculture.

The high-temperature combustion industry and transport contribute 13% of the total reactive nitrogen species generated. Accordingly, policymakers must take a comprehensive, systemic approach to nitrogen pollution. A holistic strategy that maps the factors contributing to inefficient nitrogen management is essential. This approach enables the drafting of robust policies that promote sustainability without compromising economic viability.

Collective Global Response to Nitrogen Pollution

Although the issue of nitrogen pollution has long been recognised by the scientific community and policymakers, global action on this critical yet often overlooked environmental challenge was initiated with the adoption of the UNEA 4/14 Resolution on Sustainable Nitrogen Management during the 4th United Nations Environment Assembly in 2019. The resolution recognises nitrogen’s essential role in global food security and its harmful environmental impacts when mismanaged. The resolution calls for integrated nitrogen management strategies, enhanced nitrogen use efficiency, and sustainable agricultural practices. It also underscores the importance of research, innovation, and international cooperation to support developing countries in implementing these practices.

Building on this foundation, the 2nd Resolution on Sustainable Nitrogen Management in the 5th UNEA, held in 2021 and 2022, took concrete steps to operationalise these commitments. Establishing the Working Group on Nitrogen Management was a key development, tasked with creating an action plan, identifying policy gaps, and proposing solutions. The Working Group’s summary report (UNEP, 2024) highlighted the need for specific policy recommendations, robust monitoring and reporting mechanisms, and strengthened international cooperation. The Working Group Report mentions inter-alia that countries should develop comprehensive voluntary national action plans. The elements of the voluntary action plans are given below:

Finally, the case of nitrogen pollution is a classic one where science is clear and policymakers have been aware of the problem for a long time, however, the action on the ground is not commensurate with the problem. One of the most important tasks is to unmask the causes and effects of nitrogen pollution through effective communication among all stakeholders and citizens.

Addressing nitrogen pollution requires a comprehensive strategy that combines a global approach with a national perspective, engaging all relevant stakeholders. Policymakers, scientists, technologists, farmers, and the industry must collaborate on a multi-stakeholder action agenda to tackle this complex issue effectively. This should be underpinned by robust communication efforts that convey the scale and scope of nitrogen pollution to all involved parties. By fostering cooperation and informed decision-making, we can develop and implement sustainable solutions that mitigate the environmental impacts of nitrogen, ensuring a healthier planet for future generations.

References:

1. Changing the approach: turning nitrogen pollution into money. (n.d.). UNEP. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/changing-approach-turning-nitrogen-pollution-money

2. Chen, J., & Wei, X. (2018). Controlled-Release Fertilizers as a Means to Reduce Nitrogen Leaching and Runoff in Container-Grown Plant Production. In InTech eBooks. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.73055

3. Erisman, J. W., Galloway, J., Seitzinger, S., Bleeker, A., & Butterbach-Bahl, K. (2011). Reactive nitrogen in the environment and its effect on climate change. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 3(5), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2011.08.012

4. Fowler D, Coyle M, Skiba U, Sutton MA, Cape JN, Reis S, Sheppard LJ, Jenkins A, Grizzetti B, Galloway JN, Vitousek P, Leach A, Bouwman AF, Butterbach-Bahl K, Dentener F, Stevenson D, Amann M, Voss M. The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013 May 27;368(1621):20130164. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0164. PMID: 23713126; PMCID: PMC3682748.

5. Galloway, J. N., Townsend, A. R., Erisman, J. W., Bekunda, M., Cai, Z., Freney, J. R., Martinelli, L. A., Seitzinger, S. P., & Sutton, M. A. (2008). Transformation of the Nitrogen Cycle: Recent Trends, Questions, and Potential Solutions. Science, 320(5878), 889–892. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1136674

6. Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser and Pablo Rosado (2022) - “Fertilizers” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/fertilizers' [Online Resource]

7. Hannah Ritchie, Pablo Rosado and Max Roser (2023) - “Agricultural Production” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/agricultural-production' [Online Resource]

8. Kanter, D.R., Chodos, O., Nordland, O. et al. Gaps and opportunities in nitrogen pollution policies around the world. Nat Sustain 3, 956–963 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0577-7

9. Luo, M., Moorhead, D. L., Ochoa‐Hueso, R., Mueller, C. W., Ying, S. C., & Chen, J. (2022b). Nitrogen loading enhances phosphorus limitation in terrestrial ecosystems with implications for soil carbon cycling. Functional Ecology, 36(11), 2845–2858. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14178

10. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2021). Happening Now: Dead Zone in the Gulf 2021. oceantoday.noaa.gov. https://oceantoday.noaa.gov/deadzonegulf-2021/#:~:text=The%202021%20Gulf%20of%20Mexico,and%20thirty%20four%20square%20miles.

11. Overview of Greenhouse Gases | US EPA. (2024, April 11). US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases#:~:text=Nitrous%20oxide%20(N2O,as%20during%20treatment%20of%20wastewater.

12. Portmann RW, Daniel JS, Ravishankara AR. Stratospheric ozone depletion due to nitrous oxide: influences of other gases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012 May 5;367(1593):1256-64. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0377. PMID: 22451111; PMCID: PMC3306630.

13. Raghuram N, Aziz T, Kant S, Zhou J and Schmidt S (2022) Editorial: Nitrogen Use Efficiency and Sustainable Nitrogen Management in Crop Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 13:862091. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.862091

14. Richardson K, Steffen W, Lucht W, Bendtsen J, Cornell SE, Donges JF, Drüke M, Fetzer I, Bala G, von Bloh W, Feulner G, Fiedler S, Gerten D, Gleeson T, Hofmann M, Huiskamp W, Kummu M, Mohan C, Nogués-Bravo D, Petri S, Porkka M, Rahmstorf S, Schaphoff S, Thonicke K, Tobian A, Virkki V, Wang-Erlandsson L, Weber L, Rockström J. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci Adv. 2023 Sep 15;9(37):eadh2458. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adh2458. Epub 2023 Sep 13. PMID: 37703365; PMCID: PMC10499318.

15. Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K. et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461, 472–475 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a

16. Sutton, M. & Billen, Gilles & Bleeker, Albert & Erisman, Jan Willem & Grennfelt, P. & Grinsven, Hans & Grizzetti, B. & Howard, Clare & Leip, Adrian. (2011). European nitrogen assessment - Technical summary. European Nitrogen Assessment. XXXV-LI.

17. The European Nitrogen Assessment. (2011). In Cambridge University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511976988

18. Tian, H., Pan, N., Thompson, R., Canadell, J., Suntharalingam, P., Regnier, P., Davidson, E., Prather, M., Ciais, P., Muntean, M., Pan, S., Winiwarter, W., Zaehle, S., Zhou, F., Jackson, R., Bange, H., Berthet, S., Bian, Z., Bianchi, D., . . . Zhu, Q. (2024). Global nitrous oxide budget (1980–2020). Earth System Science Data, 16(6), 2543–2604. https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-16-2543-2024

19. Townsend, A. R., Howarth, R. W., Bazzaz, F. A., Booth, M. S., Cleveland, C. C., Collinge, S. K., Dobson, A. P., Epstein, P. R., Holland, E. A., Keeney, D. R., Mallin, M. A., Rogers, C. A., Wayne, P., & Wolfe, A. H. (2003). Human Health Effects of a Changing Global Nitrogen Cycle. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 1(5), 240. https://doi.org/10.2307/3868011

20. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. (2021). Report of the Task Force on Reactive Nitrogen*. In unece.org (ECE/EB.AIR/WG.5/2021/2). UNECE. Retrieved May 28, 2024, from https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/ECE_EB.AIR_WG.5_2021_2-2102622E.pdf

21. United Nations Environment Programme (2019) Chapter 4. The Nitrogen Fix: From Nitrogen Cycle Pollution to Nitrogen Circular Economy - Frontiers 2018/19: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/27543

22. United Nations Environment Programme (2024). Summary of the Work of the UNEP Working Group on Nitrogen. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/44579.

23. United Nations Environment Programme, Global Partnership on Nutrient Management, & International Nitrogen Initiative (2013). Our Nutrient World: The Challenge to Produce More Food and Energy with Less Pollution. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/10747.

24. Wang, M., Houlton, B. Z., Wang, S., Ren, C., Van Grinsven, H. J., Chen, D., Xu, J., & Gu, B. (2021). Human-caused increases in reactive nitrogen burial in sediment of global lakes. ˜the œInnovation, 2(4), 100158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100158

25. World Health Organisation, Ambient (Outdoor) Air Pollution. UNDRR. (2018) http://www.undrr.org/quick/78500

Leave a comment