Sri Lanka is currently facing its worst economic crisis since the country gained independence in 1948. Huge piles of foreign debt, a series of lockdowns, soaring inflation, shortage in fuel supply, fall in foreign currency reserves and devaluation of the currency have adversely impacted the country’s economic growth. In the face of a worsening economic and humanitarian crisis, Sri Lanka axed an ill-conceived national experiment in organic agriculture during the winter of 2021. With riots breaking out across the country and curfews being imposed to contain them, the question has to be asked, what set fire to Sri Lanka?

Scene 1: The Run Up

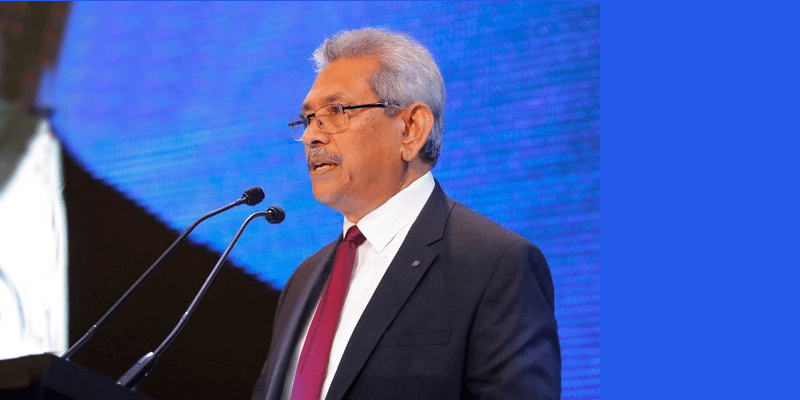

In his 2019 election campaign, Sri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa promised to transition the country’s farmers to organic agriculture over a ten-year period. Rajapaksa’s government followed through on that promise last April, imposing a nationwide ban on the import and use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides and ordering the country’s 2 million farmers to go organic.

The result was a disaster and a very swift one at that. Despite claims that organic farming can produce comparable yields to conventional farming, Sri Lanka observed a fall of over 20% in the first six months itself. The country, which had previously been self-sufficient in rice production, was forced to import $450 million worth of rice, even as domestic prices for this staple of the national diet surged by around 50 percent.

Tea, the nation’s primary source of foreign exchange suffered too. This prompted the Rajapaksa government to partially lift its fertilizer ban on key export crops, including tea, rubber, and coconut in November 2021. Faced with heavy backlash in the form of angry protests, soaring inflation, and the collapse of Sri Lanka’s currency, the government finally suspended the policy for several key crops like tea, rubber, and coconut in February 2022, although it continues for some others.

Human costs have been even greater. Prior to the pandemic outbreak, the country had proudly achieved upper-middle-income status. Today, half a million people have been forced to sink back into poverty. Soaring inflation and a rapidly depreciating currency have forced Sri Lankans to cut down on food and fuel purchases as prices surge. The nation ran out of its diesel reserves on the 31st of March, forcing people to abandon their vehicles in long queues next to the refuelling stations. To keep things from falling apart, the government decided to offer $200 million in direct compensation to farmers, as well as an additional $149 million in price subsidies to rice farmers who have suffered losses. This hardly compensated for the harm and suffering caused by the ban. Farmers have widely criticised the payments for being vastly insufficient and excluding many farmers, particularly tea producers, who provide one of the most important sources of employment in rural Sri Lanka. The drop in tea production alone is estimated to result in $425 million in economic losses.

The farrago of magical thinking, technocratic haughtiness, ideological delusion, self-dealing, and sheer shortsightedness that produced the crisis in Sri Lanka implicates both the country’s political leadership and advocates of the so-called sustainable agriculture: the former for seizing on the organic agriculture pledge as a myopic measure to slash fertilizer subsidies and imports and the latter for suggesting that such a transformation of the nation’s agricultural sector could ever possibly succeed. The arrogant belief in one’s plan and ignorance towards very apparent red flags set Lanka on fire before, as it is now, a few millennia later.

Scene 2: Rajapaksa Rings the Bell

Sri Lanka’s journey through the organic agriculture looking glass began in 2016 itself with the establishment, at Rajapaksa’s behest, of a new civil society movement known as Viyathmaga. On its website, Viyathmaga describes its mission as harnessing the “nascent potential of the professionals, academics and entrepreneurs to effectively influence the moral and material development of Sri Lanka.” The movement set the stage for Rajapaksa’s rise to prominence as an election candidate and facilitated the creation of his electoral platform. As he prepared for his presidential run, the movement produced the “Vistas of Prosperity and Splendour,” a sprawling agenda for the nation that encompassed everything from national security to anticorruption to education policy, alongside the promise to transition the nation to fully organic agriculture within a decade.

(Source: Lanka Eyewitness)

Despite Viyathmaga’s claims to technocratic expertise, most of the country’s leading agricultural experts were kept out of policy formation and decision making. The finally crafted platform included promises to phase out synthetic fertilizer, develop 2 million organic home gardens to help feed the country’s population, and turn the country’s forests and wetlands over to the production of biofertilizers.

Following his election as the President in 2019, COVID-19 arrived. The pandemic crumbled Sri Lanka’s tourism sector, which accounted for almost half of the nation’s foreign exchange in the previous year. This pushed the country into a severe debt trap as it failed to repay its Chinese creditors following a binge of infrastructure development over the previous decade. Still, could be worse?

Enter Rajapaksa’s organic pledge. Sri Lanka has subsidised farmers’ use of synthetic fertilizer since the early days of the Green Revolution in the 1960s. The results in Sri Lanka, as in much of South Asia, were astounding: rice and other crop yields more than doubled. After experiencing severe food shortages as recently as the 1970s, the country became food secure, and tea and rubber exports became critical sources of exports and foreign reserves. Rising agricultural productivity enabled widespread urbanisation, and much of the country’s labour force entered the formal wage economy, culminating in Sri Lanka’s official upper-middle-income status in 2020.

By 2020, the total cost of fertilizer imports and subsidies was close to $500 million each year. With fertilizer prices skyrocketing, the tab was likely to increase further in 2021. By banning synthetic fertilizers, Rajapaksa was allowed to kill two birds with one stone: improving the country’s foreign exchange situation while also cutting a massive subsidy expenditure from the pandemic-hit public budget.

Unfortunately, however, there’s no free lunch when it comes to agricultural practices. Inputs like chemicals, nutrients, land, labour, and irrigation bear a critical relationship to the agricultural output. From the very announcement of the plan, agricultural experts and agronomists from Sri Lanka and the rest of the world started to ring the alarm bells. They warned that the crop yields would significantly decrease if Sri Lanka transitions to organic farming. In response to such concerns, the government stated that it would increase the production of manure and other organic fertilizers to replace imported synthetic fertilizers. However, there was no conceivable way the country could produce enough fertiliser on its own to compensate for the shortfall.

So the plan, in the end, was only sold to blind believers of organic farming, most of whom were involved in businesses that benefitted from the fertilizer ban. The false economy of banning imported fertilizer hurt the Sri Lankan people dearly. The revenue loss from tea and other export crops outweighed the reduction in currency outflows caused by the ban on imported fertiliser. The increased import of rice and other food stocks pushed the bottom line even lower. The cost of compensating farmers and providing public subsidies for imported food eventually dwarfed the budgetary savings from cutting subsidies. Sri Lanka found itself in the quicksand of never-ending misery.

Scene 3: Farming Isn’t Rocket Science

It is well known that organic farm yields are significantly (19-25%) lower and prices are higher. What is less known are the reasons for the high yields of chemical farming. As the yield rises, the prices decrease; a simple demand-supply fundamental. The green revolution has three pillars, irrigation, chemical inputs, and pesticides, and each of them has played its role in weakening the natural environment. India too observed an alarming decrease in ground-water levels due to the high irrigation requirement of High Yielding Variety (HYV) crops. Fertilizer overuse has polluted ground and surface water, and high nitrate levels are causing eutrophication and disrupting aquatic ecosystems. Chronic renal failures in Sri Lanka have been linked to cadmium contamination in water from fertiliser run-off, and pesticides have been linked to an increase in the incidence of some cancers. Hundreds of farmers die each year while spraying them in their fields.

In a nutshell, the costs of HYVs are ‘externalised’ to the natural environment. Individuals who suffer from health problems bear these costs, as do taxpayers when the government spends their money on pollution reduction. As a result of the externalised costs, the prices of chemical farm produce remain artificially low. If the Sri Lankan government advisory team did not consider the impending price increase of organic farm produce, they would be completely naive. What was labelled “low yield” by the green revolution was far less extractive of soil nutrients. This type of farming demanded much less cash for inputs, which meant farmers borrowed less.

Beginning in the nineteenth century, the expansion of global trade enabled the importation of guano (mined from ancient deposits on bird-rich islands) and other nutrient-rich fertilizers from far-flung regions onto farms in Europe and the United States. This, along with a series of technological innovations—better machinery, irrigation, and seeds—allowed for higher yields and labour productivity on some farms, which freed up labour and thus launched the beginning of large-scale urbanisation, one of the defining features of global modernity.

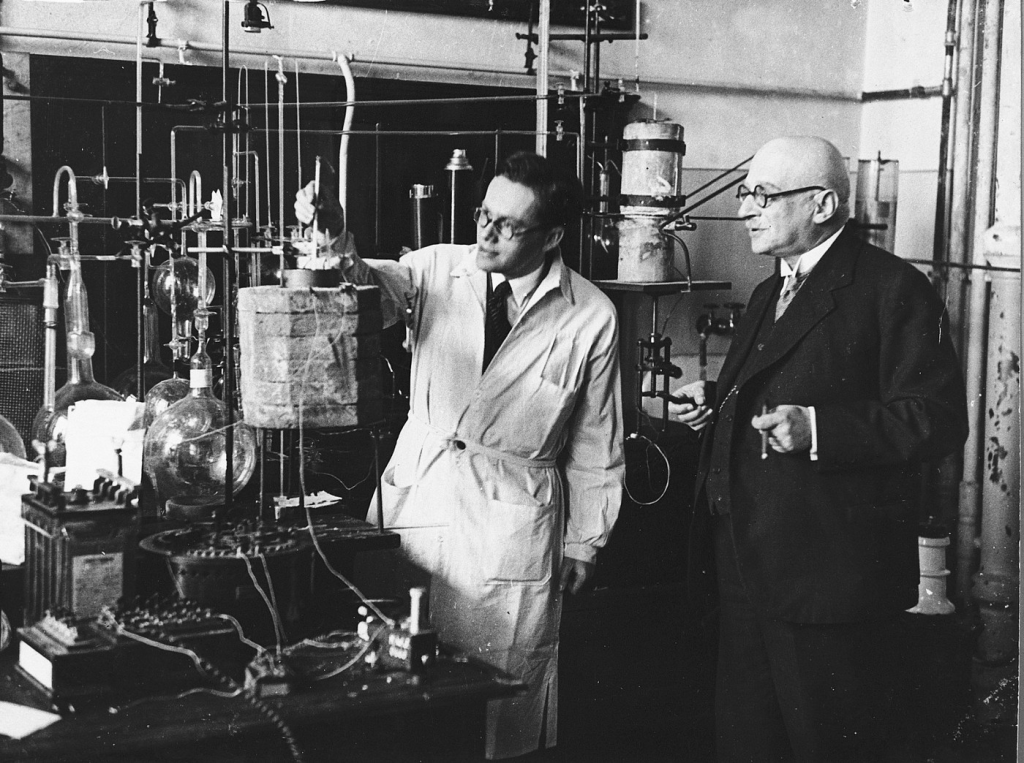

However, the biggest development in the golden tale of farming occurred with the invention of the Haber-Bosch process by German scientists in the early 1900s, which uses high temperature, high pressure, and a chemical catalyst to pull nitrogen from the air and produce ammonia, the basis for synthetic fertilizers. Synthetic fertilizers, therefore, changed the course of global agriculture, and the pace of development and in turn reshaped human society. The widespread use of synthetic fertilizers in most countries has resulted in a rapid increase in yields and a shift in human labour away from agriculture and toward sectors with higher incomes and a higher quality of life.

(Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

After World War II, as synthetic fertilizers became more widely available around the world and were combined with other innovations such as modern plant breeding and large-scale irrigation projects, something remarkable happened: Human populations more than doubled, but agricultural output tripled on only 30% more land thanks to synthetic fertilizers and other modern technologies.

The advantages of synthetic fertilizers, on the other hand, extend far beyond simply feeding people. It is not an exaggeration to say that without synthetic fertilizers and other agricultural innovations, there would be no urbanisation, industrialization, global working or middle class, or secondary education for the majority of people. This is because fertiliser and other agricultural chemicals have replaced human labour, freeing up vast populations from having to devote the majority of their lifetime labour to food production.

Scene 4: Debt, Danger and Discourse: A dream with unimaginable social, political, and economic costs

According to major Sri Lankan tea conglomerate Herman Gunaratne, one of 46 experts picked by President Rajapaksa to spearhead the organic shift, the move’s consequences for the country are unimaginable. The ban drew the tea industry into complete disarray. By going completely organic, they were predicted to lose 50 percent of the crop but certainly would not have got 50 percent higher prices for the same.

According to Gunaratne, the ban will cut the country’s average annual tea production of 300 million kg in half. Furthermore, because organic tea is ten times more expensive to produce, its market is also limited. Estimates show that tea is Sri Lanka’s single largest export, bringing in more than $1.25 billion per year, accounting for nearly 10% of the country’s export income. Former central bank deputy governor W.A. Wijewardena is said to have called the organic plan a “dream with unimaginable social, political, and economic costs.” He stated that Sri Lanka’s food security has been “compromised,” and that the situation is “worsening day by day” due to a lack of foreign currency.

Virtually the entirety of organic agriculture production serves two populations at opposite ends of the global income distribution. At one end are the 700 million or so people globally who still live in extreme poverty. They include the poorest farmers in the world who spend their lives growing enough food to feed themselves. They forgo synthetic fertilisers and most other modern agricultural technologies not by choice, but because they cannot afford them. They are entombed in a poverty trap, unable to produce enough agricultural surplus to make a living selling food to others; thus, they cannot afford fertiliser and other technologies that would allow them to increase yields and produce a surplus. On the other end are rich people who hold romanticised ideas about agriculture and its allied practices. They look at the natural world with rose-tinted glasses. For them consuming organic food is a lifestyle choice tied up with notions about personal health and environmental benefits, for which, they are ready to spend more money. Because almost none of these consumers of organic foods grow the food themselves. Organic agriculture for these groups is a niche market. Albeit, a lucrative one for many producers, accounting for less than 1 percent of global agricultural production.

So as long as organic farming remains a niche in its larger counterpart, everything stays streamlined. Although the yields are low, the producers save up on the money invested in buying fertilizers and in return, privileged consumers pay a premium for products labelled organic. Yields are not disastrously lower too, because there are ample nutrients available to smuggle into the system via manure. As long as organic food remains niche, the relationship between lower yields and increased land use remains manageable.

Scene 5: Fundamental Miscalculations

The ongoing catastrophe in Sri Lanka, though, shows why extending organic agriculture to the vast middle of the global bell curve, attempting to feed large urban populations with entirely organic production, cannot possibly succeed. According to a report, this transition would have led to a tremendous fall in yields of up to 50 percent for tea and corn and 30 percent for coconut.

The economics of such a transition is not just daunting; they are impossible. Importing fertilizer is expensive, but importing rice is far more costly. Sri Lanka, meanwhile, is the world’s fourth-largest tea exporter, with tea accounting for a lion’s share of the country’s agricultural exports, which in turn account for 70 percent of total export earnings.

Photo: maheshg/Shutterstock

When it is evident that farm output will decline, it is critically important for a small country like Sri Lanka to consider what percentage of its farms produce ‘real’ food and how much is used for plantations. Food cannot be substituted with tea, rubber, cashew, coconut, sugarcane, or oil palm. Agricultural activities are carried out on 41.63 percent of Sri Lanka’s total land area. Of this, 23.45 percent is dedicated to paddy and other field crops, while 10.32 percent is dedicated to plantations. Considering a consistently lower yield of paddy in Sri Lanka compared to international averages, this land was certainly not sufficient to stockpile supplies for a primarily rice-eating nation.

Another problem is that, as generations of farmers have adopted green revolution farming, the skills and knowledge required for organic farming are scarce today. As revealed in one survey that showed that only 20 percent of farmers had the knowledge to transition to completely organic production and 63 percent of respondents did not receive any guidance on organic cultivation. The biggest blind spot was observed when experts realised that any effort to produce enough manure to sustain the nationwide organic farming programme would require a vast expansion of livestock holdings, with all the additional environmental damage that would entail. There is almost certainly not enough land in the small island nation to produce that much organic fertilizer.

A survey also revealed that many key crops in Sri Lanka depend on heavy use of chemical input for cultivation, with the highest dependency in paddy at 94 percent, followed by tea and rubber at 89 percent each. According to an estimate, the country generates about 3,500 tonnes of municipal organic waste every day. About 2-3 million tonnes of compost can be produced from this on an annual basis. However, just organic paddy cultivation requires nearly 4 million tonnes of compost annually at a rate of 5 tonnes per hectare. For tea plantations, the demand for organic manure could be another 3 million tonnes.

Conclusion:

This fiasco of a nationwide experiment to completely transition to organic farming boils down to a simple math problem. A math problem, which at its core, is ideological. Organic agriculture is a global ideological movement that is innumerate and unscientific by design, promoting fuzzy statistics and poorly specified claims about the possibilities of alternative food production methods. The simplest way one can see this problem is the ignorance of the fact that relatively simple biophysical relationships govern what goes in; what comes out. What Rajapaksa forgot is that any agricultural system can produce socioeconomic and political outcomes on a global scale.

Rajapaksa maintains that his policies have not failed. Even though Sri Lanka’s agricultural production was collapsing, he attended the United Nations climate change summit in Glasgow, Scotland, late last year. When he wasn’t dodging protests, he touted his nation’s commitment to an agricultural revolution allegedly “in sync with nature.”

With the onset of the spring harvest this year, the bans on fertilizers have been lifted, although, the subsidies on them are yet to be restored. Unfortunately, however, irrespective of all this happening, Rajapaksa established yet another committee to advise the government on potential methods of increasing organic fertilizer production. He and his advisors are still in denial of the realities that constrained their agricultural economy. The advocates of organic agriculture have also been silent on this issue.

One may argue that the problem was not with the organic practices they touted but with the precipitous move to implement them inefficiently amid a crisis. The farmers were, after all, left uneducated about the methods of organic farming. But although the immediate ban on fertilizers was ill-conceived, the truth is that no major agrarian nation has still transitioned to a completely organic method of farming. Because all that organic agriculture offers as Sri Lanka’s disaster has laid bare for all to see, is misery.

As we now know that agriculture is a double-edged sword. On one hand, organic farming hurts the economy and the population by producing a crisis, on the other hand, we observe synthetic fertilizers taking a toll on the health of the individuals spraying and indirectly consuming them. The solution, therefore, lies in the hands of bioengineering and other modern scientific methods to produce microbial soil treatments that fix nitrogen in the soil or genetically modified crops that use fewer pesticides and fertilizers. What the world can learn from this episode, is that one should avoid taking hasty unscientific decisions, because in the end, like in Sri Lanka, they might lead to a cascade of events that will hurt everyone brutally.

(Photo by Anna Maria Barry-Jester for the Center for Public Integrity.)

Leave a comment