The dreadful Bengal famine occurred amid World War II, only four years before independence. As India turns 75, the occasion calls for many celebrations, one of which is India’s journey from growing more food to smartly growing it. During the British Raj, India’s grain economy hinged on a unilateral exploitative relationship. As a result, the weakened country quickly became vulnerable to periodic famines, financial instabilities, and low productivity. The need of the hour, therefore, was a life-saving miracle to pull the country out of starvation. Enter, Green Revolution.

Scene 1: History

India endured two severe droughts in 1964-65 and 1965-66, resulting in food shortages and famines among the country’s increasing population. India’s famines before independence were exacerbated by British taxes and agrarian policies in the 19th and 20th centuries. Marginal farmers found it difficult to obtain financing and credit at reasonable rates from the government and banks, and hence became easy prey for money lenders. They borrowed money from landlords, who imposed exorbitant interest rates and eventually forced the farmers to work in their fields to repay the loans. Before the Green Revolution period, proper financing was not provided, causing many challenges and hardships for Indian farmers. Traditional farming practices in India offered insufficient food production in the context of the country’s fast-rising population. By the 1960s, India’s low production had resulted in more severe food grain shortages than in other developing countries.

The year was 1965 when the then Prime Minister of India, Congress leader Lal Bahadur Shastri, called upon international donor agencies (like the Ford and Rockefeller Foundation) and the most brilliant of minds across India, to bring the Indian population out of misery. At the forefront of this plan was Mankombu Sambasivan Swaminathan, a geneticist who had always been a close observer of agricultural sciences. Born in Kumbakonam, Madras Presidency to a general surgeon father, Dr. M. K. Sambasivan. His parents desired that he pursues a career in medicine. With this in mind, he began his higher study in zoology. However, after witnessing the effects of the Bengal famine of 1943 during World War II and rice shortages throughout the subcontinent, he resolved to devote his life to ensuring India had enough food. Despite his family history and the fact that he grew up in an era when medicine and engineering were considered far more respectable, he chose agriculture. He is now known as the father of the Indian Green Revolution.

He wasn’t the only great mind involved though, people like Chidambaram Subramaniam, who was the food and agriculture minister at the time, a Bharat Ratna, known as the Political Father of the Indian Green Revolution were also involved. Dilbagh Singh Athwal, popularly known as the Father of Wheat Revolution and scientists such as Atmaram Bhairav Joshi also contributed to making the Green Revolution a success. Institutions such as the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI) gave these scientists and all other allied people and agencies a platform to work on. And so by the end of 1966 began the Green revolution, which lasted until 1978. It changed India’s status from being a food-deficient economy to one of the world’s leading agricultural nations.

Scene 2: Green Revolution

India has the world’s second-largest agricultural land, with 20 agro-climatic regions and 157.35 million hectares under cultivation. Even though India is no longer an agrarian economy, agriculture remains important to 58% of rural families. With all the agricultural potential, India yet has 195.9 million undernourished people lacking sufficient food to meet their daily nutritional requirements, India has one-quarter of the world’s hungry population; anaemia affects 58.4% of children under the age of five, while 53% of women and 22.7% of men in the age group of 15-49; 23% of women and 20% of men are thin, and 21% of women and 19% of men are obese.

This twelve-year plan was launched to address India’s hunger crisis. The main plan revolved around three major criteria, using seeds with improved genetics (High Yielding Variety seeds), double cropping in the existing farmland and continuing the expansion of farmland. The Green Revolution was, therefore, mostly a successful campaign in Northern India. Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh, for example, were able to reap the benefits of the green revolution and achieve rapid economic development, while other states could only manage a modest increase in agricultural production.

The HYV seeds were more effective and successful with the wheat crop in places with abundant irrigation. As a result, the Green Revolution was initially concentrated on areas with better infrastructure, such as Tamil Nadu and Punjab. The high-yielding variety seeds were sent to other states during the second phase, and crops other than wheat were included in the plan. Proper watering is the most crucial condition for high-yielding variety seeds. Crops cultivated from HYV seeds require a lot of water, and farmers can’t rely on the monsoon. As a result, the Green Revolution enhanced irrigation systems surrounding fields in India. Cotton, jute, oilseeds, and other commercial and cash crops were not included in the plan. The green revolution in India was primarily focused on food grains such as wheat and rice. It increased the availability and use of fertilisers, weedicides, and pesticides to reduce crop damage or loss. It also aided in the promotion of commercial farming in the country with the introduction of machinery and technology such as harvesters, drills, and tractors.

Scene 3: The Aftermath

The Green Revolution significantly increased agricultural production. Food-grain output in India increased dramatically. Wheat cultivation benefited the most from the revolution. During the early stages of the plan, crop production increased to 55 million tonnes. Not only did the revolution enhance agricultural output, but it also increased the per acre yield. In its early stages, the Green Revolution increased wheat production per hectare from 850 kg/hectare to an astonishing 2281 kg/hectare. With the onset of the Green Revolution, India achieved self-sufficiency and became less reliant on imports. The country’s production was enough to fulfil the expanding population’s needs and to reserve it for emergencies.

However, the grass wasn’t green throughout. The Green Revolution, along with it brought its own set of downsides. Rice, millets, sorghum, wheat, maize, and barley were the principal crops planted in the period preceding the Green Revolution, and rice and millets were grown more than wheat, barley, and maize combined. However, millet output has declined, and crops that were formerly consumed in every household became fodder crops just a few decades after the Green Revolution. Meanwhile, many traditional rice types consumed previous to the Green Revolution are no longer available, and the number of available local rice varieties has reduced to 7000, with not all of these varieties under production. Thus, since the 1970s, India has lost about 1 lakh indigenous rice varieties that evolved over thousands of years. This loss of species is primarily due to the government’s emphasis on the cultivation of subsidised high-yielding hybrid crops and the emphasis on monoculture.

The government-initiated policies enhanced rice, wheat, lentils, and other crop output, resulting in food self-sufficiency in the country. However, it also depleted the available gene pool. The use of fertilisers, insecticides, and groundwater resources enhanced crop yield. Mismanagement and abuse of chemical fertilisers, pesticides, and a lack of crop rotation, on the other hand, caused the soil to become infertile, and groundwater loss became a typical occurrence in agricultural areas. These consequences made farmers even more miserable since they had to spend more money on crop cultivation to compensate for these deficiencies.

The Green Revolution had numerous ecological and societal consequences. Loss of indigenous landraces, loss of soil nutrients rendering it unproductive, and excessive use of pesticides led to the prevalence of pesticide residues in foods and the environment. Farmers were forced to switch to unsustainable practices to enhance production. There were increased suicide cases among farmers who were unable to cope with rising farming costs and loan debts. Small farmers sold their farms to larger commercial farmers and were unable to survive food inflation and the economic crisis. Thus farmers abandoned farming and pursued other vocations later.

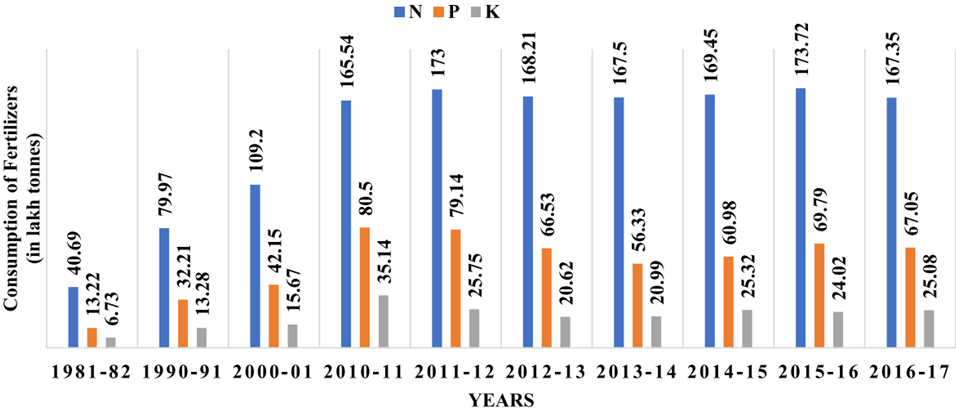

The consumption of N, P, and K fertilizers increased steadily post-Green Revolution era. In particular, the period after 2000-2001 saw increased consumption of inorganic fertilizers, as the application of inorganic fertilizers influenced crop yield. Nitrogen-based fertilizers such as urea, ammonia, and nitrate were widely used. The uncontrolled use of these N, P, and K adversely affected the fertility of the soil and altered the microbiota of the soil. (Source: Nelson et al.)

Following the Green Revolution, the agricultural land area expanded from 97.32 million hectares in 1950 to 126.04 million hectares in 2014. Since the 1950s, the area under cultivation of coarse cereals has declined dramatically, from 37.67 million hectares to 25.67 million hectares. Similarly, sorghum farming declined from 15.57 million hectares to 5.82 just million hectares, while pearl millet cultivation decreased from 9.02 million hectares to 7.89 million hectares. However, rice, wheat, maize, and pulse farming grew from 30.81 million hectares to 43.95 million hectares, 9.75 million hectares to 31.19 million hectares, 3.18 million hectares to 9.43 million hectares, and 19.09 million hectares to 25.23 million hectares, respectively.

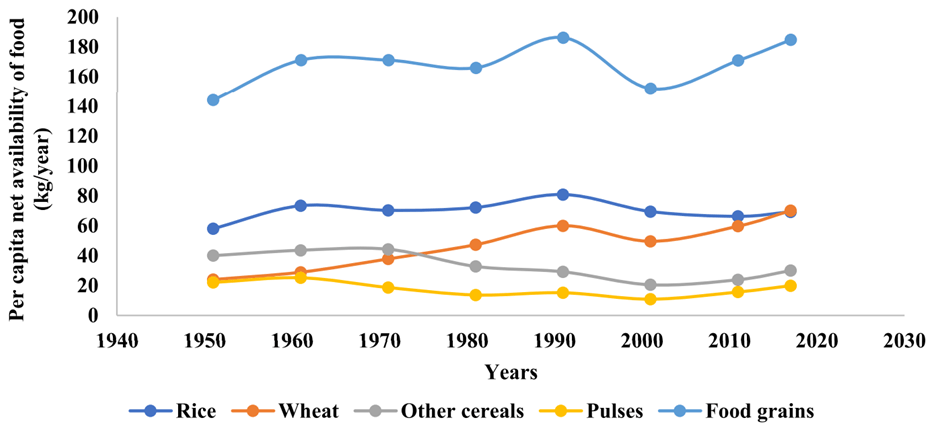

The availability of food grains impacted the consumption and nutrition patterns of the Indian population. Food grain net availability per capita has increased over time. Rice availability per capita grew from 58.0 kg/year in 1951 to 69.3 kg/year in 2017. Rice per capita net availability reached an all-time high in 1961. Similarly, per capita net wheat availability rose from 24.0 kg/year in 1951 to 70.1 kg/year in 2017. However, the net availability of other cereal grains, such as millets and pulses, has dropped over time. This resulted in a shift in consumption patterns over time, as well as a shift in emphasis from minor grains and pulses to major cereals, rice and wheat. The change in nutrition and eating patterns on a larger scale contributed to the onset of nutritional deficiencies in both, the rural and urban populations.

Scene 4: The Present and What Lies Ahead

Because of the Green Revolution, technology and other parts of agricultural strategy and policy, the country’s per capita food output has more than doubled in the last 50 years, despite a 237 percent rise in population. However, agriculture now faces a new set of issues. Production or growing food isn’t that much of a problem, but how to grow it smartly using lesser natural resources while ensuring that growers of food are adequately remunerated is a bigger challenge.

A significant and sustained rise in farmer income, as well as agricultural change, necessitate a paradigm shift in approach. Changes to antiquated legislation and liberalisation of the sector are required. Advances in science-led technology, a stronger role for the private sector in both the pre- and post-harvest phases, liberalised output markets, active land lease markets, and an emphasis on efficiency will better equip agriculture to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century. To ensure that agriculture progresses to the next stage of development, the Centre and the states need to coordinate their actions and strategies.

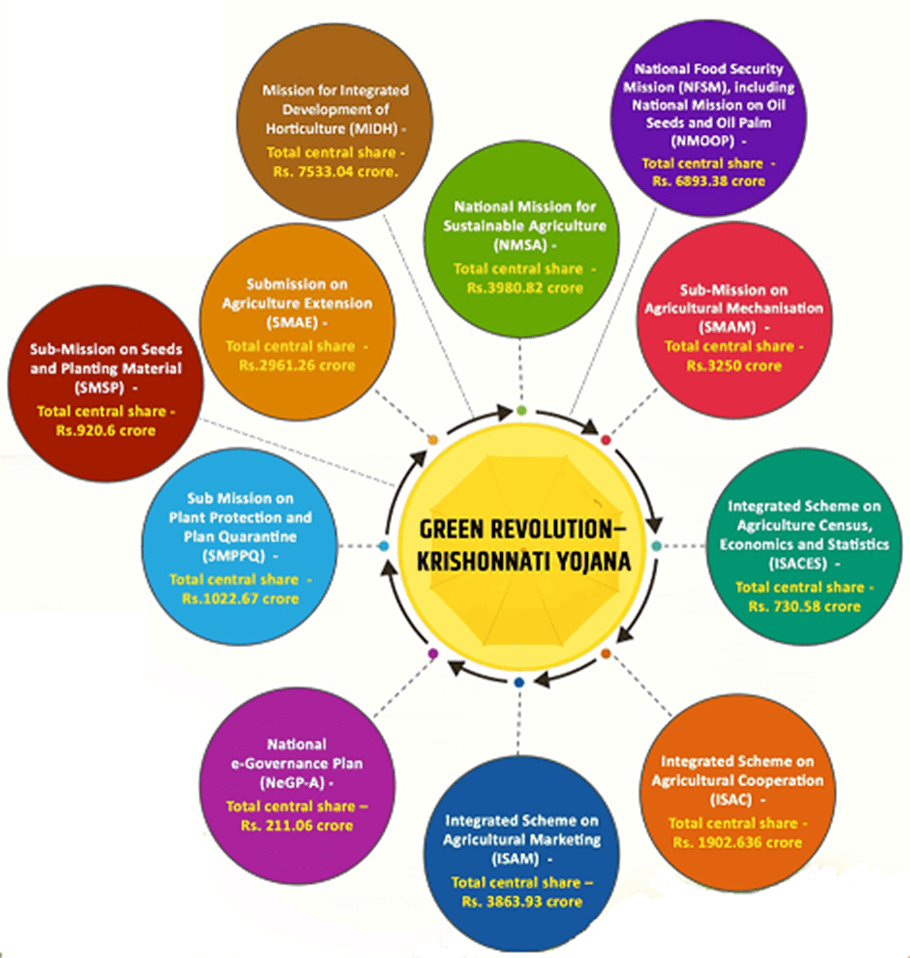

Prime Minister Narendra Modi approved the Green Revolution Umbrella Scheme – ‘Krishonnati Yojana’ in the agriculture sector for three years, from 2017 to 2020, with a Central Share of Rs. 33,269.976 crores. The Green Revolution- Krishonnati Yojana umbrella scheme includes 11 schemes that aim to develop the agriculture and allied sector scientifically and holistically to increase farmers’ income by increasing productivity, production, and better returns on produce, strengthening production infrastructure, lowering production costs, and marketing agriculture and allied produce.

Scene 5: Conclusion: A Great Nation Was Not Born 75 Years Ago

The independent India was not born great. The transfer of power from the British Raj did not give her freedom from famine, plagues and poverty. But no story of greatness begins great. It speaks of triumphs, struggles, plot twists and milestones alongside the blood, sweat and tears shed to achieve them. India’s tale of the Green Revolution is as much about M.S. Swaminathan as it is about the millions of farmers and the billions of consumers, you and me. It is a tale of pulling millions of Indians out of the mouth of starvation. It is a tale of nutrition, public health, economy, trade and everything in between. While no plan is perfect, and this one certainly wasn’t, what we should remind ourselves is that without the Green Revolution things could’ve taken a turn for the worse.

The indiscriminate use of chemical fertilisers, pesticides, and weedicides, development of irrigation, and crop specialisations favouring a few crops, which were the primary sources of agricultural growth after the Green Revolution, wreaked havoc on natural resources, the environment, and ecology. Heavy subsidies and free power supply for irrigation led to reckless, indiscriminate, and abuse of water, resulting in major distortions in crop choices. In most crops, increased productivity has been matched by an increase in average production cost. With all these downsides, what the Green Revolution prevented was mass famines and starvation. It prevented food scarcity as we see in post-Rajapaksa Sri Lanka. It prevented what could’ve turned into a huge loss of lives to hunger. The Green Revolution ensured, in some sense, that no child remains impoverished and no person has to sleep hungry.

The last band in the Indian flag is green in colour showing the fertility, growth and auspiciousness of the land. The Green revolution only helped the last band become greener. What lies ahead is a future of development. While most farmers are now moving out of the agrarian sector, it is believed that this migration is necessary to develop the allied agricultural fields. The future will come about more reliably if policies to improve agricultural production and incomes are pursued today. May our motherland prosper, forever.

Jai Hind.

Leave a reply to Ayushi Cancel reply