Cancer knows no borders, but its impact varies greatly depending on where you live. In developed countries, the threat of cervical cancer is relatively low, thanks to widespread screening programs and preventative measures. However, in developing nations like India, cervical cancer is a public health crisis of epic proportions. Shockingly, one-quarter of all global cases of cervical cancer occur in India, where it’s responsible for up to 29% of all female cancers. Despite the overwhelming statistics, there’s no nationwide screening program in place, and the disease continues to claim lives at an alarming rate. In fact, cervical cancer is now the cause of death for 1 in 6 Indian women diagnosed with cancer between the ages of 30 and 69. It is estimated that cervical cancer will occur in approximately 1 in 53 Indian women during their lifetime compared with 1 in 100 women in more developed regions of the world. Cervical cancer, although preventable and curable, is the second most common cancer in Indian women. The time for action is now.

Scene 1: Cervical Cancer and its Epidemiology

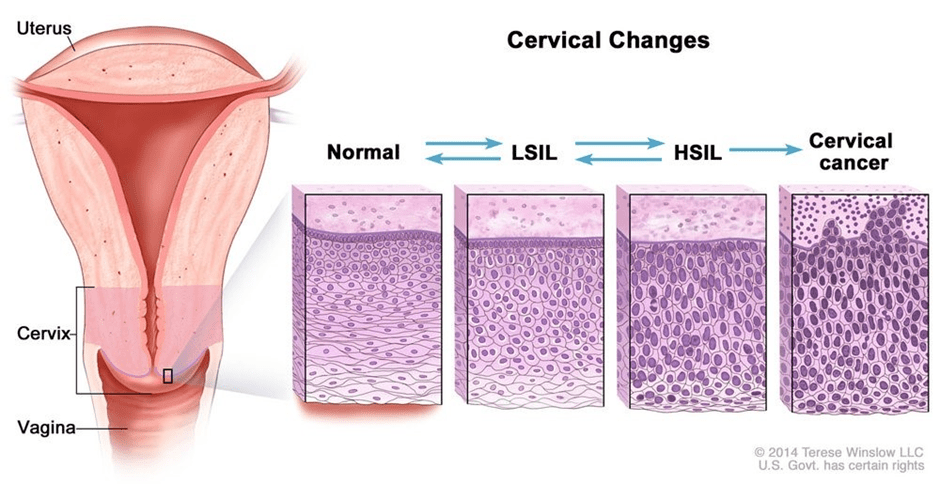

Women’s reproductive organs can be affected by five main types of cancer, namely cervical, ovarian, uterine, vaginal, and vulvar cancer. Cervical cancer is a condition that arises from the rapid multiplication of healthy cells in the cervix, which is the lower and narrower end of the uterus, caused by the Human Papillomavirus (HPV). This can result in the formation of either a cancerous or benign tumor. While initially non-cancerous, these abnormal changes can gradually develop into cervical cancer. The removal of precancerous tissue is essential to prevent the development of cancer. However, if the precancerous cells continue to grow unchecked, they can invade deeper tissues and organs, resulting in invasive cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer can be broadly classified into two types based on the type of cell where the cancer begins. The first type is squamous cell carcinoma, which originates from the thin, flat cells that line the surface of the cervix, is the most common type of cervical cancer accounting for 80 to 90 percent of all cases. The second type is adenocarcinoma, which is less common, and begins in the glandular cells that produce mucus in the cervical canal, making up about 10 to 20 percent of all cervical cancers. Knowing the type of cervical cancer is important as it can influence the treatment approach recommended by healthcare providers.

The progression of cervical cancer is well-documented, with a persistent infection of high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) being the necessary cause. Other factors such as early age at first sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, and sexually transmitted infections can also facilitate the initiation and progression of the disease. HPV is a small, double-stranded DNA virus with over 100 distinct types, but HPV 16 and 18 are responsible for over 70% of invasive cervical cancers globally, with even higher rates in India. However, there is a window of opportunity to detect and treat pre-invasive neoplasia with outpatient treatment modalities, as cervical cancer has a long pre-invasive phase that lasts for 10-15 years.

The incidence and mortality of cervical cancer depend on available resources and medical infrastructure for population-wide screening and treatment. It’s worth noting that prophylactic HPV vaccines contain both types of HPV responsible for the majority of cervical cancer cases. By taking advantage of early detection and vaccination, we can combat the spread of cervical cancer and ultimately save lives.

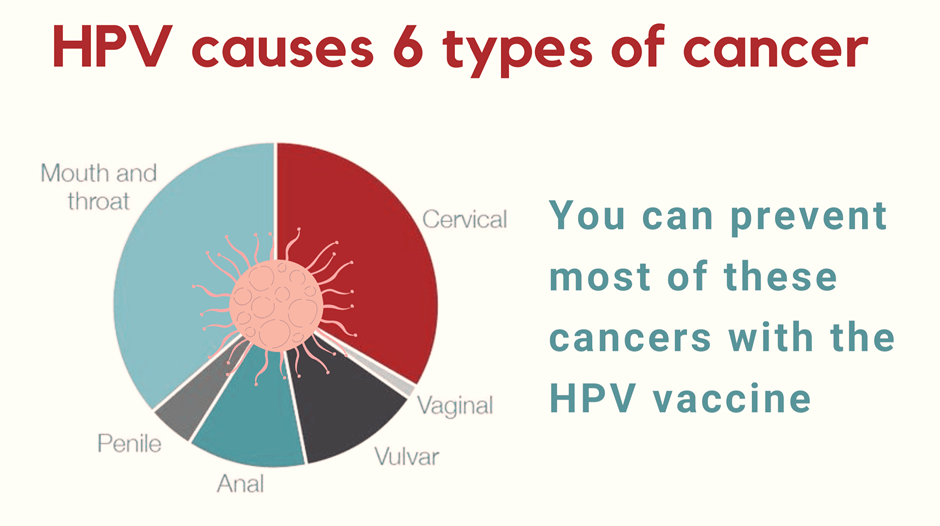

Men are also at risk of developing HPV-associated cancers of the mouth and throat, penis, and anus from specific strains of the HPV virus. However, unlike women, there are no existing tests for HPV available for men. HPV infection can lead to the development of cancer in various parts of the body and has become a growing concern in recent years. Research shows that certain strains of the virus can cause severe health issues in both men and women, making it imperative to take proactive measures to protect against the virus. The absence of HPV testing for men can complicate early detection and treatment, and further research is needed to develop effective screening and prevention strategies for this vulnerable population.

Scene 2: The Call for Elimination of Cervical Cancer

In May 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) set a goal to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem by using widespread HPV vaccination, screening, early diagnosis, and treatment of cervical pre-cancer and cancer. The World Health Assembly (WHA), then launched a global strategy to implement this goal on November 17, 2020, with 194 countries showing support for the program despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The targets of the elimination program are to have 90% of girls fully vaccinated with two doses of HPV Vaccine by the age of 15, 70% of women screened with a high-performance test at the ages of 35 and 45, and 90% of women with cervical pre-cancer and cancer receiving treatment to reach a goal of fewer than four cases per 100,000 women. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 aim to reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment, with elimination targets playing a significant role in achieving this goal.

Effective implementation of both aspects of cervical cancer prevention – HPV vaccination and screening linked with the treatment of pre-cancers – can lead to a substantial reduction in the incidence and mortality rates of the disease, ultimately eradicating it as a public health problem. However, developing countries like India are posed with several challenges such as cultural barriers, low awareness, inadequate access to healthcare, and limited resources and infrastructure that must also be addressed to achieve this goal.

Higher incidence and mortality rates due to cervical cancer have been observed among socio-economically disadvantaged women in rural areas. However, even a single round of screening has proven to significantly reduce the incidence and mortality of the disease. Unfortunately, many rural women lack awareness of the risk factors associated with cervical cancer and have limited access to formal education. Knowledge, attitude, and practice surveys have indicated that younger and more literate women have better awareness and knowledge of the disease than their older and illiterate counterparts. To address this disparity, various screening strategies have been implemented, with a particular focus on rural populations. These efforts aim to increase awareness of cervical cancer risk factors and provide better access to screening services, ultimately reducing the incidence and mortality of the disease.

Screening:

Regular screening is crucial in detecting cervical cancer at an early stage, when it is most treatable. The Papanicolaou (Pap) smear test, also known as cervical cytology, is the standard diagnostic tool used for cervical cancer screening. During the procedure, a sample of cells is collected from the cervix using a swab or spatula and examined under a microscope by a cytologist. A negative result indicates the absence of infection, while a positive result indicates the presence of precancerous or cancerous cells. If a positive result is obtained, a follow-up test (mostly an HPV typing test) is typically performed to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any errors.

According to the American Cancer Society, women between 21 to 29 years of age should receive a Pap test every three years if the result is normal. For women aged 30 to 65 years, an HPV test should be done along with a Pap smear test. If both tests are normal, women can wait five years until their next screening. Alternatively, if only an HPV test is done and is normal, women can also wait for five years until the next screening. If only a Pap smear test is done and is normal, women should wait three years until their next Pap test. Screening is not required, however, if a hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) is done. By following these guidelines and receiving regular screening, women can significantly reduce their risk of developing cervical cancer and catch any abnormalities before they progress into cancer.

In addition to the Pap test, various other tests are used to diagnose cervical cancer. These include a bimanual pelvic examination, colposcopy (which helps guide biopsy of the cervix), biopsy, MRI to measure the tumor’s size, PET scan, and biomarker testing of the tumor. These tests are crucial in detecting cervical cancer and determining the best course of treatment for the patient. A combination of these tests is often used to achieve an accurate diagnosis and develop a treatment plan that is tailored to the individual’s needs.

HPV Vaccination:

In India, two globally licensed vaccines are accessible: the quadrivalent (HPV4) vaccine (marketed by Merck as GardasilTM) and the bivalent (HPV2) vaccine (marketed by Glaxo Smith Kline as CervarixTM). These vaccines are created using recombinant DNA technology, which results in the production of non-infectious virus-like particles (VLPs) composed of the HPV L1 protein. Another nonavalent vaccine (marketed by Merck as Gardasil9TM) is available as the first gender-neutral HPV vaccine in India. The indigenous HPV vaccine developed by the Serum Institute of India, called CERVAVAC, is likely to be rolled out by mid-2023.

- Bivalent (HPV2): this vaccine contains HPV types 16 and 18

- Quadrivalent (HPV4): this vaccine contains HPV types 6, 11,16 and 18

- Nonavalent (HPV9): this vaccine contains HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58. This vaccine is expected to broaden the protection against cervical cancer by ~15%.

In India, the Bivalent and Quadrivalent HPV vaccines are predicted to prevent approximately 83% of cervical cancers, while the Nonavalent vaccine is anticipated to prevent approximately 98% of cervical cancers. All three vaccines are highly effective in preventing cervical cancers caused by the HPV types contained in the vaccine.

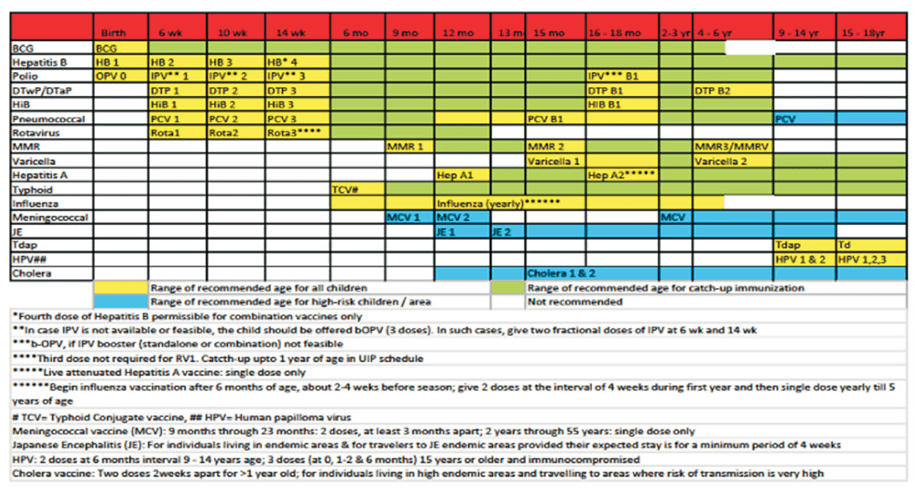

The Indian Academy of Pediatrics suggests the following schedule for administering HPV vaccines.

- Girls between 9 to 14 years of age should receive two doses of the vaccine with an interval of 6 months between them.

- For girls aged 15 and above, three doses are recommended with the schedule being 0-1-6 months for Cervarix and 0-2-6 months for Gardasil.

- For immunocompromised individuals, regardless of age, the recommended schedule is also three doses with 0-1-6 months for Cervarix and 0-2-6 months for Gardasil.

- HPV9 is licensed in a three-dose schedule of 0-2-6 months for females aged 9-26 years and males aged 9-15 years.

It is ideal to start the vaccination schedule at 9-10 years of age since the prevention of disease is better if started earlier and young adolescents mount a superior immune response compared to older individuals. Additionally, the Tdap vaccine and HPV vaccines can be given simultaneously.

Scene 3: The Challenges

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), India is at risk of having almost 225,000 new cases of cervical cancer every year by 2025 unless prevention and screening efforts are widely implemented. Sadly, there is currently no national screening program in place for cervical cancer in India. Pap smear cytology services are available at only select laboratories in urban areas and the quality of these tests can vary greatly. Routine screening for asymptomatic women is not common in Indian populations, and women are often only advised to undergo a Pap smear test if they have symptoms.

Health System

An effective health system is a vital component of any population-based screening program, which requires competent health personnel, resources and capacity, and coordinated service delivery. However, many low- and middle-income countries encounter infrastructure-related challenges such as inequitable service delivery, low adoption of recommendations, lack of trained experts, and insufficient financing. India’s healthcare system is especially complex and its quality can vary significantly from state to state, making it difficult to implement a nationwide screening program. Health coverage and quality of care in India are also fragmented, with notable disparities between states, socioeconomic groups, castes, and rural and urban areas. India has recently taken steps to improve and monitor the quality of healthcare despite its challenges.

Awareness Isn’t Translated Into Screening

A significant obstacle to cervical cancer screening is the insufficient awareness and knowledge about the prevention and treatment of cervical cancer and HPV among the community. Studies have shown a discrepancy between the awareness of cervical cancer and the actual uptake of screening among women in the community. Although many women have heard of cervical cancer, only a few are familiar with its symptoms and have undergone screening. Nevertheless, a considerable number of women are willing to participate in screening despite the low uptake.

The consensus among the scientific community, therefore, is that there is a need for enhanced health education about cervical cancer and the significance of screening for both urban and rural women in India.

Stigma, Logistical, Awareness and Cultural Barriers

Several researchers have identified various barriers that prevent women from undergoing cervical cancer screening in India. These barriers range from perceived low risk and fear to misunderstanding and stigma. This stigma was often rooted in a fear of transmission of cancer, a sense of personal responsibility for having caused the cancer, and a fear of the inevitability of disability and death following a cancer diagnosis. A 2015 study conducted in Karnataka found that cost and low perceived risk were the most common barriers to cervical cancer screening and vaccination. In this study, 60% of the women did not have health insurance and could not always afford medical visits, and only 5% had undergone a Pap smear.

Another study explored the barriers to cervical cancer screening among two different groups of women in India: those who had purposefully opted out of the screening and those who were willing but could not attend for various reasons. The main reasons why women purposefully opted out of screening were reluctance to go through a test that could detect cancer and a lack of understanding of the need to visit a health professional despite a lack of symptoms. Women who were willing but could not go for screening faced other barriers, including family obligations and a lack of approval from their husbands.

Child marriages also increase the risk of exposure to and transmission of HPV and cervical cancer. In India, at least 15 lakh girls under 18 years of age get married every year. HPV vaccination can have long-term benefits in preventing cervical cancer in this at-risk population and reducing the overall cancer burden.

The perception that HPV is solely a sexually transmitted disease also discourages discussions around the importance of vaccination. Lastly, misinformation about vaccines is prevalent, further discouraging uptake.

Cost of HPV Vaccine

Although the HPV vaccine has been available globally since 2006 and has been proven to be effective, it is still not widely accessible due to various challenges. One major obstacle is the high cost of the vaccine, particularly in developing countries like India. The quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil Merck) is priced at ₹2,800 per dose, and the bivalent vaccine (Cervarix from GlaxoSmithKline) is priced at ₹3,299 per dose. This makes it difficult for the vaccine to be included in government-funded programs, such as the Universal Immunization Program.

Scene 4: The Way Forward

To address the significant burden of cervical cancer in India, investing in an HPV immunization program could prove beneficial, particularly for the at-risk population of girls under 18 years of age who are exposed to HPV through child marriages. India has demonstrated success in running immunization programs on a large scale, as evidenced by the success of the ‘Pulse Polio Immunization programme’ and the formation of a cold chain for vaccine transportation and achieving full coverage of all districts in India by 1990 under the Universal Immunization Program.

The success of the world’s largest COVID-19 vaccination drive, which utilized digital platforms such as Co-WIN to track and ensure vaccination coverage, further strengthens India’s ability to implement an effective HPV vaccination program. Adapting these digital platforms to track HPV vaccination beneficiaries’ eligibility and coverage could increase the program’s effectiveness in reducing the burden of cervical cancer in India. The inclusion of the HPV vaccine in the Universal Immunization Program run by the Indian government will help provide the vaccine at subsidized costs, if not for free, helping the vaccination program reach larger masses and thereby reducing the burden of cervical cancer in India.

India is making significant efforts to combat cervical cancer by introducing vaccination for girls aged 9 to 14 years through schools. To fight against cervical cancer, India is planning to launch CERVAVAC, an indigenous vaccine developed by the Serum Institute of India, by mid-2023. The vaccine is predicted to be priced between ₹200 and ₹400 and has been approved by the Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI) and cleared by the National Technical Advisory Group for Immunisation (NTAGI) for use in the Universal Immunisation Programme (UIP). The vaccination will primarily be provided in schools, but the government has emphasized that girls who do not attend school will also be vaccinated through community outreach and mobile teams. This is a crucial step as research has shown a connection between cervical cancer incidence and human development index values, with lower rates observed as HDI rises.

National cancer control programs can help overcome public health barriers through a multi-level strategy. At the primary level, Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) provide door-to-door information, education, and communication, while health workers conduct mass recruiting campaigns and screening camps. At the secondary level, gynaecologists trained in colposcopy, colposcopy equipment, a pathologist, chemotherapy, and palliative care services are provided, with district-level monitoring. At the tertiary level, training is improved at regional cancer centres with an emphasis on surgical skills, and infrastructure is established for radiation and imaging techniques.

The screening of cervical cancer has undergone a significant change with the introduction of non-cytological screening by HPV test and Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid (VIA), which has been implemented in rural areas where cytology facilities are scarce. HPV vaccination has multiplied the efforts over the last decade. However, despite all these advancements, screening for cervical cancer will remain necessary, as millions of women have already been exposed to the virus. Therefore, a new standard of care in cervical cancer prevention should include widespread vaccination and the HPV test as a point-of-care test.

Conclusion: Empowering Women Begins With Better Healthcare

It is unfortunate that cervical cancer, despite being preventable, ranks second in terms of incidence and mortality among Indian women, only behind breast cancer. Women are typically diagnosed with cervical cancer in their mid-50s, but precancerous changes are often detected in their 20s and 30s. The incidence of cervical cancer reaches its highest point between the ages of 51 to 60, after which it gradually declines with advancing age. The fact that precancerous changes are typically identified at a younger age compared to when cancer is diagnosed, emphasizes the gradual progression of cervical cancer and underscores the possibility of its prevention through timely interventions.

The story of minimizing the burden of cervical cancer in India, therefore, begins at the age of 9. Getting vaccinated against HPV with only three doses ensures that the woman is saved from an unfortunate and preventable death due to cancer. It ensures that every person, institution, and family who is linked with that woman, don’t suffer. One famous slogan, “Healthy Women, Healthy World”, embodies the fact that as the custodians of health and welfare, women play a crucial role in ensuring the well-being and health of their families and communities. However, due to their many responsibilities, women often prioritize the healthcare needs of their loved ones over their own, neglecting their health. It is therefore essential that women’s health and well-being are prioritized, as many illnesses affecting women, including cervical cancer, can be prevented with proper care and attention.

The key to battling the stigma attached to the talk about female reproductive health in India lies in increasing awareness about the same. The process of destigmatization of menstrual health has achieved tremendous success in rural areas and areas with lower literacy rates because of the efforts of NGOs, ASHA volunteers and all the other governmental and non-governmental stakeholders. A similar process can be followed in order to ensure that women are educated about their reproductive health. Women and men in schools must be provided with an open platform to discuss health with professional healthcare providers. It is important to ensure that men are educated about female reproductive health as well, as to further ensure the destigmatization of such issues in both urban and rural populations.

With efforts like the inclusion of the HPV vaccine in the Universal Immunization Program of the Indian government, improved and regular screening programs and widespread vaccination drives, India is all set to reduce its cervical cancer burden. It is in the hands of the government, policymakers, non-governmental stakeholders, scientists, healthcare providers and women and men to ensure that no woman has to die from cervical cancer.

Disclaimer:

This blog post is intended for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While the information provided in this post is based on reputed scientific and print media resources and is factually correct to the best of our knowledge, readers should not rely solely on this information for their medical decisions. It is important to consult a qualified healthcare provider for any medical information, including information related to cervical cancer, diagnosis, and vaccination.

Leave a reply to Nimisha Cancel reply