Biotechnology today has managed to synthesize life-saving pharmaceuticals using bacteria, more nutritious crops that are resistant to pests and bacteria that eat plastic. Driven by the need to solve some of the world’s most pressing issues, innovators have paved the way for Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), offering an unimaginable range of advantages. We find GMOs physically present in farmers’ fields, supermarkets and based on where you live, on the carts of vegetable vendors. Today, however, GMOs have made their way symbolically in addressing pressing global issues, and rhetorically in scientific and policy circles, public discourses and comment sections on social media platforms. Due to the intricate nature of the topic, there exists a significant variation in public perception towards GMOs, which varies greatly with geography, age, and gender. This raises the question of the underlying reasons behind the regional discrepancies in GM product adoption. In this essay, we aim to investigate these potential biases and gain a deeper understanding of the factors that contribute to them.

We are fortunate to have the valuable insights of Prof. Kent J. Bradford, Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of California, Davis, who graciously agreed to provide us with answers to the questions I presented to him. His expertise will greatly enhance our understanding of the subject, and his responses can be found later in this post.

Scene 1: History

GMOs have recently gained considerable attention, however, it is important to note that humans have been altering the genetic makeup of organisms for over thirty thousand years [1], long before the existence of scientific laboratories capable of directly manipulating DNA. While not influencing the genetic makeup of an organism directly, our ancestors used methods of “selective breeding” or “artificial selection” as a means to manipulate the genetic makeup of the resultant progeny to favour desired traits. Although artificial selection is not commonly considered GMO technology in modern times, it served as the precursor to modern genetic engineering processes and was the earliest instance of human intervention in genetic modifications.

In 1973, the field of GMO technology witnessed a significant breakthrough when Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen successfully engineered the first genetically engineered (GE) organism [2]. The scientists developed a method to precisely cut out a gene from one organism and insert it into another, ultimately transferring a gene encoding antibiotic resistance from one strain of bacteria to another. This process conferred antibiotic resistance upon the recipient bacteria. Following this achievement, Rudolf Jaenisch and Beatrice Mintz [3] utilized a similar method to introduce foreign DNA into mouse embryos, marking another important milestone in the development of GMO technology.

The emergence of GE technology caused a buzz among various stakeholders, including the media, scientists, and government officials, who were concerned about its potential impact on human health and the environment [4]. As a result, in 1974, a moratorium on GE projects was imposed, and the Asilomar Conference of 1975 was organized by Paul Berg, to deliberate on the safety of GE experiments [5]. During the three-day conference, experts discussed the risks and benefits of GE technology and ultimately agreed to proceed with caution under certain safety and containment regulations [6]. These regulations were designed to evolve over time as the scientific community advanced. The groundbreaking transparency and cooperation demonstrated at the conference won support from governments worldwide, opening the doors to a new era of modern genetic modification.

Scene 2: Enter, Agribiotech

Our ancestors have manipulated plants through selective breeding for decades of thousands of years in order to create desired traits. With advancements in technology, the 20th century saw a surge in agricultural biotechnology, which focused on selecting traits like increased yield, pest resistance, and abiotic stress tolerance. In 1994 the Flavr Savr, a genetically modified tomato with delayed ripening became the first commercially grown GM food crop and by 2003, over 7 million farmers worldwide were cultivating GM crops. Notably, more than 85% of these farmers were located in developing nations. [7]

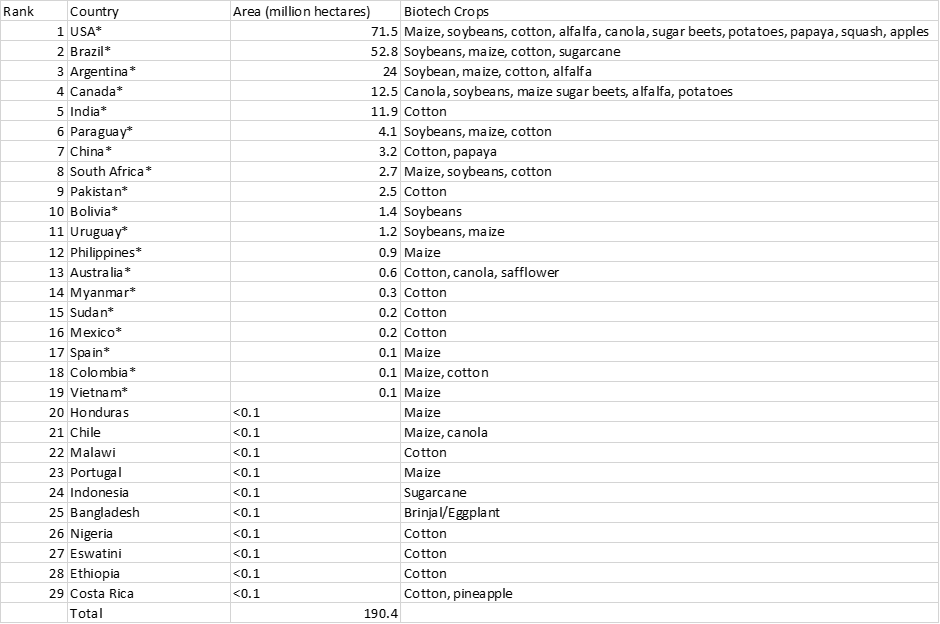

In 2019, the adoption of GM crops globally showed a slight decline, with a total of 190.4 million hectares being grown across 29 countries. This represented 1.3 million hectares (3.2 million acres) or 0.7% decrease from the 2018 figures. Despite this small decrease, the overall trend in biotech crop adoption remains positive, with significant growth over the past few decades.

2019 also marked the 24th year of commercialization of GM crops. The top five countries growing GM crops had reached close to GM crop-specific saturation in the area under cultivation for these GM crops. For example, for India, Bt cotton accounted for 94% of the area under cultivation of the crop [10]. The average biotech crop adoption rate in these countries had increased to reach close to saturation, with the United States leading the pack at 95% (average for soybeans, maize, and canola adoption), followed by Brazil (94%), Argentina (~100%), Canada (90%), and India (94%) for the crops available in these countries [10]. This high level of adoption suggests that further expansion of biotech crop areas in these countries would readily occur following approval and commercialization of new GM crops and traits for increased production of nutritious food, as well as mitigating problems related to climate change accompanied by the emergence of new pests and diseases.

The technology remains a promising solution to some of the challenges facing agriculture today. GM crops can be tailored to address specific environmental and economic conditions, allowing farmers to grow crops that are more resistant to pests and diseases, require fewer pesticides, and produce higher yields. These benefits make GM crops attractive for farmers, particularly those in developing nations where access to advanced farming techniques is often limited. Overall, the continued adoption and expansion of GM crops will be a critical factor in meeting global food security challenges in the years to come.

As a result, biotechnology has become increasingly beneficial to more than 1.95 billion people in these five countries, representing 26% of the current world population of 7.6 billion. Moreover, public sector institutions have conducted biotech crop research on crops such as rice, banana, potato, wheat, chickpea, pigeon pea, and mustard, which have various economically-important and nutritional quality traits that can benefit food producers and consumers in developing countries. [10]

*19 biotech mega-countries growing 50,000 hectares, or more, of GM crops

**Rounded off to the nearest hundred thousand [10]

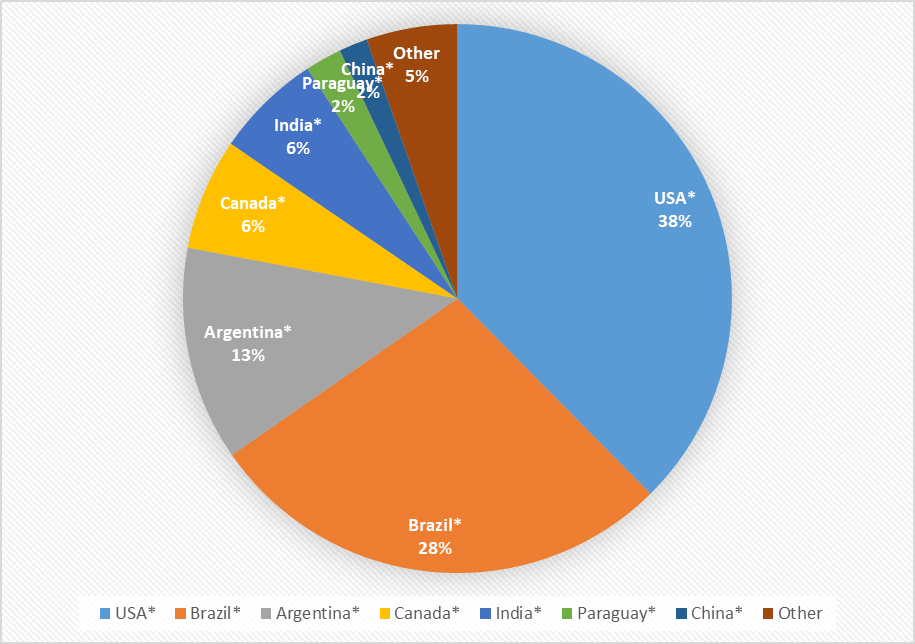

Figure 4 illustrates the proportion of total crop area under cultivation of GM crops globally, with the USA having the largest area at 38%, followed by Brazil at 28%, and Argentina at 13%. Notably, the EU does not have any area under cultivation of GM crops. It is also worth noting that despite extensive research in biotechnology, China has only 2% of the global area under cultivation of GM crops. Figure 3 shows that the USA, Brazil, Canada, and Argentina have GM food crops, while India does not have any GM food crops under cultivation. The geographic variation in the adoption of GM crops and the preference for GM non-food vs. food crops is a paradox that requires further examination of underlying factors.

Scene 3: The Paradox in the Adoption of GM Crops

Figures 3 and 4 also provide insights into the disparities between countries in their adoption of GM crops, particularly in terms of GM food crops versus GM non-food crops. Notably, the United States, Argentina, Brazil, and Canada have cultivated both types of GM crops. Despite global recognition of the importance of innovation for food security and significant public and private investments in agribiotechnology research for over three decades, there is still no consensus among countries on the adoption of GM crops. This presents a paradox, where significant investments have been made in the agribiotech sector, yet widespread adoption of GM crops has not been achieved.

Numerous studies have examined the adoption of GM crops in various regions and have identified several factors that may influence their uptake. These factors include public attitudes, varying scientific evidence, the presence and robustness of regulatory frameworks, businesses involved in GM crop production, and labelling mechanisms to aid informed consumer choice.

Regulatory Frameworks

Regulations governing genetically modified (GM) foods vary significantly worldwide. Several European countries, including France and Germany, have prohibited the cultivation of GM crops. In contrast, the United States, Brazil, Canada and Argentina generally have more progressive regulations regarding GM crops and are among the leading producers of such crops.

Amongst various possible reasons for not adopting or adopting GM crops in a restricted manner, the regulatory regime seems to be a major guiding force for public opinion. Regulatory approaches regarding the adoption of genetically modified (GM) crops fundamentally embrace the application of the “precautionary principle.” The varying regulations governing genetically modified (GM) foods worldwide may contribute to the differences in public opinion. For example, the EU and several European countries have not allowed the cultivation of GM crops, which may lead to more widespread scepticism about the safety of GM foods. Meanwhile, countries with progressive regulations, such as the United States and Brazil, tend to have more positive attitudes towards GM crops. However, it’s important to note that when GM crop cultivation is not permitted in a given country, public opinion is not based on actual experience with those crops. In this context, the regulatory situation embodies the precautionary principle, irrespective of the opinions of the populations. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that while GM crop cultivation is not permitted in the EU, the import of animal feed derived from GM crops grown in the US and Brazil is allowed.

Exploring the general public perception in countries with restrictive regulatory regimes towards GM crop adoption could shed light on whether a more cautious approach is observed among the public.

Public Opinion

‘Public opinion’ refers to the “representation of public consciousness or will, anything acted upon or expressed in public.[11]” Despite the complexity of the issue, it is noteworthy that GMOs are said to have elicited polarized opinions. People are typically portrayed as either entirely for or against GMOs, with limited consideration for conditional support or opposition based on specific contexts. Developing an informed opinion on GMOs requires taking into account a range of contentious issues, such as corporate control, world hunger, human rights, moral implications, the validity of scientific research, government and international regulations, and GMOs’ role in addressing these problems.

People who support genetically modified organisms (GMOs) believe this technology can help increase food production for a growing global population based on current scientific research. On the other hand, people who oppose GMOs are usually worried about corporate control of the food supply, believing that the potential risks associated with the widespread use of GMOs have not been adequately addressed by current research. They base their reasoning on the precautionary principle, which advocates for caution and careful consideration before taking action.

The Pew Research Center published an article titled “Many publics around world doubt safety of genetically modified foods” [12] in 2020 suggesting that there is widespread concern about genetically modified foods globally. According to the article, approximately 50% of people surveyed in 20 different countries worldwide believe that genetically modified foods are unsafe to consume based on a survey conducted by them between October 2019 and March 2020.

In general, both men and women consider genetically modified (GM) foods to be unsafe. However, women are more likely than men to express concern about their safety. According to the same survey, in 12 of the 20 countries, a greater percentage of women than men believe GM foods are unsafe to eat, suggesting a possible sex-linked bias.

The Pew Research Center published a report on the “Public opinion about genetically modified foods…” in 2016[13]. The report presents that a significant percentage of Americans (39%) believe that GM foods are more detrimental to health. Younger adults are more likely to perceive GM foods as health risks than their older counterparts. About 48% of those between the ages of 18 and 29 believe that GM foods are worse for one’s health than non-GM foods, compared to only 29% of those 65 and older.

Possible Biases against GMOs

Bias may be generated in the mind of the general public due to the polarization of media, which can influence people’s attitudes and beliefs. A view is also held that advocacy groups such as Greenpeace, and Organic Consumers Association, and other stakeholders, provide biased and one-sided information against the adoption of GM crops. However, some studies suggest that the media is becoming less polarized and increasingly favourable about the GMO debate over time [14]. A study by the Pew Research Center [12], showed that people who had taken science courses were more open towards GM crops. However, the public perception in the US and the EU with respect to GM crops cannot be fully explained based on citizens being more aware about the science of GM crops. The different regulatory approaches taken by the EU and the US can also not be fully explained based on educational and socioeconomic position.

The socioeconomic status of a country could also be a contributing factor, but studies have found that people living in countries with low standards of living, high rates of undernourishment, and a strong economic dependence on agricultural output tend to be more optimistic about GM foods [15]. The same study suggested that opinions towards genetically modified food are determined less by individual trust or education, but rather by the societal benefits people receive from agricultural biotechnology.

Finally, there may be policy or regulatory bias by governments, as seen in the differing approaches taken by the EU and the US. However, it is worth noting that there are still a group of stakeholders including advocacy groups who are raising concerns about the safety and efficacy of GM foods, and public opinion, although still continuing to lean more towards deeming GM foods unsafe [16], may continue to evolve as more research is conducted and information becomes available.

I posed the following questions to Professor Kent J. Bradford in order to gain some understanding with respect to the patterns observed in the adoption of GM crops in different countries, even while significant investments at financial and scientific levels are being put in this sector.

Prof. Kent J. Bradford

Distinguished Professor Emeritus

University of California, Davis

Brief Profile:

Prof. Kent J. Bradford is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of California, Davis. He founded the UC Davis Seed Biotechnology Center in 1999 and served as its director until 2019. He served as Interim Director of the UC Davis World Food Center in 2017-2018 and Associate Director in 2019-2020. He was advanced to Distinguished Professor at UC Davis in 2013 and retired as Emeritus in 2019. He was elected a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2003, and received the faculty Award of Distinction from the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences at UC Davis in 2007.

Prof. Bradford’s research interests span diverse areas of seed science from seed germination and conservation to mathematical modeling and molecular biology. As director of the Seed Biotechnology Center, he supported the creation and commercialization of new technologies to improve crop performance, quality and sustainability and the continuing education of plant breeders and seed industry professionals. He has published more than 190 peer-reviewed research and extension articles and book chapters, co-edited three books and co-authored a textbook. He taught University and Extension courses on plant physiology, seed biology, biotechnology, ethics and philosophy of science. You can find more about him at https://bradford.ucdavis.edu/.

Questions and Answers with Prof. Kent J. Bradford

Q1. Does national regulation/ban on GM crops determine the public perception toward GM crops?

Answer [Prof. Kent J. Bradford]: Certainly, a ban on GM crops would have a negative influence on public perception. People would likely assume that there must be something wrong with them or else they would not be banned. In addition, they do not have the opportunity to try them, since they are banned, and thus have no independent way to check the information they are getting. The influence of regulations that do allow production and sale depends more on what the regulations are. In most countries that theoretically allow production and sale of GM crops, the regulations require time-consuming and expensive testing and bureaucratic procedures that discourage smaller companies and innovators from even attempting to develop and market products that would be attractive to consumers. This has resulted in GM crops being associated almost entirely in the public mind with products targeted toward farmers of commodity crops, and largely associated with herbicide and insect resistances that are important to farmers but not to consumers. Initially, the US did not require labeling of food products that contain GM content, as the regulatory process was assumed to have already assured their safety. The current US law does require products of biotechnology to be labelled (as “Bioengineered”), but this does not seem to have raised much interest or concern in the public thus far since its adoption in 2022. We are seeing new products developed using GM methods targeted to consumer interests now on the market (e.g., Impossible Burgers, Arctic Apple), and they do not seem to be encountering the same type of resistance the earlier GM products did, even though they are labeled.

Q2. Do robust policies and regulations inter-alia, providing informed consumer choice, allow for the adoption of GM crops? For example USA, Canada, Brazil and Argentina.

Answer [Prof. Kent J. Bradford]: It is clear in countries with regulations that ban GM products, as in EU and other countries, there is no opportunity for consumer choice. So only in countries that allow the sale of GM foods do consumers have any choice. In those countries, such as those you mentioned, the food products that have been available have primarily been maize, soybeans or canola, which are processed and used in many diverse products. Thus, often the consumer is not making a direct choice on the basis of GM content. Instead, as the organic industry has led the opposition to GM foods, the consumer choice has been largely whether to pay the extra price for organic foods in order to avoid the possibility of eating GM foods. This is also true in the vegetables and fruits, even though virtually none have been GM to date, but the misinformation and advertising from the organic side, which bans use of GM products, have been successful in making consumers more fearful of all non-organic products (e.g., the Non-GMO Project). This is in contrast to the introduction of the insect-resistant GM eggplant in Bangladesh (and surreptitiously in India), which can be produced with greatly reduced pesticide use and is therefore much safer for the consumer as well as the farmer. Predictably, it has been strongly opposed by anti-GM groups, particularly in India, despite its greater safety for farmers, consumers and the environment. Providing informed consumer choice has not been the driving force for regulations, but rather for the most part driven by exaggerated fears promoted by anti-GM groups that were able to convince regulators to establish a very high bar for safety testing prior to marketing, even in products that are now recognized as being entirely safe.

Q3. Does awareness in the farming community of the benefit of GM crops lead to their wider adoption?

Answer [Prof. Kent J. Bradford]: There is no doubt that the better performance (yield) and economics (reduced pesticide usage or lower costs for weeding) of the GM crops that are available have resulted in almost universal adoption by farmers when such crops are permitted to be grown. The clear example is Bt cotton in India and China, as well as other countries more permissive of GM crops, where adoption by farmers was very rapid and essentially complete, as it provided resistance to very destructive pests that otherwise required high pesticide usage. While farmers did not initially like the higher cost of seed for these crops, the benefits far outweighed the costs and farmers have quickly adopted all GM crops that have been released, assuming that regulations allow production and markets are available for the products.

Q4. Does the size of landholding and practising of intensive agriculture influence the adoption of new innovations including that of GM crops by farmers?

Answer [Prof. Kent J. Bradford]: Again, this question is largely determined by the regulatory policies in place. In the US, the vast majority of farmers and of agricultural production is done by farmers utilizing intensive agricultural practices, i.e., monocultures, fertilizer, machine planting, weeding, harvesting, etc. The vast majority of them adopted GM crops when available because of their benefits. As mentioned previously, there are no GM varieties available for most crops (e.g., essentially all of the fruits and vegetables), so it is the availability of the varieties rather than farm size that is most critical in the US. In other countries like India, studies have shown that farmers of all sizes adopted, and benefitted from, switching to Bt cotton. Again, the problem is not resistance by farmers, but lack of access to varieties improved using GM due to national and international regulatory restrictions.

While not specifically about GM crops, your question implies a larger question about farming practices. Perhaps you are aware of the consequences in Sri Lanka of banning even fertilizers as well as GM crops, and mandating organic farming methods. We do not have the time to engage in such disastrous experiments if we are to adapt agriculture to feeding 9 billion people soon and continuously thereafter. We do not have the luxury to continue to ban or restrict the improvement of crops that can remain productive with less fertilizer and pesticides and across a wider range of environments due to climate change.

Q5. Do unbiased communication and free availability and accessibility of scientific data on innovations, including GM crops, help in eliminating potential biases of stakeholders in adopting such innovations?

Answer [Prof. Kent J. Bradford]: One would hope that this is the case. However, such unbiased and science-based communications are overwhelmed by the biased and misinformed propaganda promulgated by dedicated anti-GM groups such as Greenpeace. A clear example is Golden Rice, which is genetically engineered to increase the vitamin A content in the grain. Its adoption in many parts of Asia would drastically reduce vitamin A deficiency in mothers and children, and could have prevented millions of cases of blindness and death in children by now had it been allowed on the market 20 years ago when it was first developed. Instead, Greenpeace mounted a massive misinformation campaign and legal onslaught that still prevents production of this lifesaving product where it is most needed. I can turn your question around: how much would communication of this massive responsibility of Greenpeace for such illness and death of children influence stakeholders and regulators to change the laws that prevent its production and distribution to nutritionally disadvantaged women and children?

Note:

Prof. Kent J. Bradford shared some of the studies he refers to in his response to question 4 with me. These studies show that the largest numbers of GM farmers are in the less developed countries, where farm sizes are smaller. (Brookes, G. (2022) Farm income and production impacts from the use of genetically modified (GM) crop technology 1996-2020. GM Crops & Food 13, 171-195; Klümper, W. and Qaim, M. (2014) A meta-analysis of the impacts of genetically modified crops. PLoS ONE 9, e111629.)

He has also referred the readers of this blog to the Genetic Literacy Project or the Alliance for Science to find unbiased and available scientific data on the points he has put forward.

Prof. Bradford has also referred to the Sri Lankan organic farming crisis in his response, on which I wrote a blog post in April, 2022.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Prof. Kent J. Bradford for his invaluable contribution to this blog post. I am immensely thankful for his willingness to answer the questions I posed and provide his expert insights.

I am truly appreciative of Prof. Bradford’s prompt yet profound responses, which have enriched my understanding of this complex topic. His willingness to share his expertise and provide helpful suggestions with every iteration, as well as additional sources of information, has greatly enhanced the quality of this blog. I am also grateful for Prof. Bradford’s time and consideration throughout our interaction. His encouraging and motivating responses have been instrumental in inspiring me, not only in the scientific realm but also as an individual striving for knowledge and growth.

This exchange with Prof. Bradford has left an indelible impact on me, serving as a lifelong inspiration. I am honoured to have had the opportunity to connect with someone of his stature, who graciously respected my requests as a young undergraduate engineering student.

I also encourage the readers of this blog to find inspiration in the remarkable contributions that Prof. Kent J. Bradford has made to the fields of biology, agriculture, and science, some of which can be found here. Once again, I extend my heartfelt appreciation to Prof. Kent J. Bradford for his invaluable contributions and support.

References:

[1] The genomics of selection in dogs and the parallel evolution between dogs and humans: https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms2814#citeas

[2] Cohen, S. et. al. “Construction of Biologically Functional Bacterial Plasmids In Vitro.” PNAS, November 1973. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC427208/

[3] Jaenisch, R. and Mintz, B. “Simian Virus 40 DNA Sequences in DNA of Healthy Adult Mice Derived from Preimplantation Blastocysts Injected with Viral DNA.” PNAS, April 1974. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC388203/

[4] Committee on Recombinant DNA Molecules. “Potential Biohazards of Recombinant DNA Molecules.” PNAS, July 1974. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC388511/?page=1

[5] Berg, P. “Asilomar and Recombinant DNA.” Nobel Media AB, August 2004. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1980/berg-article.html

[6] Berg, P. et. al. “Summary Statement of the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA Molecules.” PNAS, June 1975. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC432675/pdf/pnas00049-0007.pdf

[7] "Agricultural Biotechnology" (PDF). cornell.edu. PBS, ABSP II, US Agency for International Development. 2004. Retrieved 1 Dec 2016. http://absp2.cornell.edu/resources/briefs/documents/warp_briefs_eng_scr.pdf

[8] Karthik, Chinnannan & Arulselvi, Padikasan & AU, Sathiya & Subramaniyan, Govindaraju. (2018). Agricultural Biotechnology: Engineering Plants for Improved Productivity and Quality. 10.1016/B978-0-12-815870-8.00006-1.

[9] Parisi, C., Tillie, P. & Rodríguez-Cerezo, E. The global pipeline of GM crops out to 2020. Nat Biotechnol 34, 31–36 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3449

[10] “ISAAA Brief 55-2019: Executive Summary Biotech Crops Drive Socio-Economic Development and Sustainable Environment in the New Frontier” (2020) https://www.isaaa.org/resources/publications/briefs/55/executivesummary/default.asp

[11] Savigny, H. (2002). Public Opinion, Political Communication and the Internet. Politics, 22(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9256.00152

[12] Many publics around world doubt safety of genetically modified foods. (2020, November 11). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/11/11/many-publics-around-world-doubt-safety-of-genetically-modified-foods/

[13] Funk, C. (2016, December 1). 3. Public opinion about genetically modified foods and trust in scientists connected with these foods. Pew Research Center Science & Society. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2016/12/01/public-opinion-about-genetically-modified-foods-and-trust-in-scientists-connected-with-these-foods/

[14] Evanega, S., Conrow, J., Adams, J., & Lynas, M. (2022, March 23). The state of the ‘GMO’ debate - toward an increasingly favorable and less polarized media conversation on ag-biotech? GM Crops & Food, 13(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645698.2022.2051243

[15] Levi, S. (2022, January). Living standards shape individual attitudes on genetically modified food around the world. Food Quality and Preference, 95, 104371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2021.104371

[16] Funk, C. (2020, March 18). About half of U.S. adults are wary of health effects of genetically modified foods, but many also see advantages. (2020, March 18). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/03/18/about-half-of-u-s-adults-are-wary-of-health-effects-of-genetically-modified-foods-but-many-also-see-advantages/

Leave a reply to A.Gupta Cancel reply