The transition to low-carbon energy systems necessitates the rapid decarbonisation of the transportation sector, which accounts for nearly one-fifth of global CO₂ emissions. Second-generation (2G) bioethanol, produced from agricultural residues such as rice straw, corn stover, and sugarcane bagasse, offers a promising, sustainable alternative to fossil fuels, with the added advantage of circumventing the food-versus-fuel and land-use change (LUC) debates associated with first-generation biofuels. This essay provides a global overview of the evolving policy landscape surrounding 2G bioethanol, highlighting key enablers and barriers to its adoption across major producing regions, including the United States, European Union, India, Brazil, and China. Through comparative analysis, the essay provides an aggregation of how supportive policy instruments, such as blending mandates, fiscal incentives, and targeted R&D funding, have increased 2G bioethanol uptake globally while identifying their critical limitations. The report concludes with policy recommendations aimed at integrating 2G bioethanol into national decarbonisation pathways while promoting rural development and agricultural circularity.

This post may differ from the usual style of haevyre.com. It takes a more in-depth, report-like approach rather than a typical blog format. The aim is to offer a concise policy-research primer on the topic, blending accessible analysis with a deeper dive into the subject matter.

Introduction

The global climate crisis, driven by cumulative greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, necessitates urgent decarbonisation to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, as outlined in the Paris Agreement. Achieving this requires global GHG emissions to peak before 2025 and decline by 43% by 2030 (UNFCCC, n.d.). Fossil fuels account for about 90% of global CO₂ emissions, with the transportation sector alone contributing one-fifth of the total (CSIRO, 2024; Hannah Ritchie, 2020). Decarbonising this sector is imperative, however challenging, due to infrastructure lock-ins and the energy density requirements for aviation, shipping, and heavy freight (Van Gogh et al., 2024).

Biofuels and Bioethanol

Biofuels are renewable energy sources derived from biomass and represent a promising alternative to conventional fossil fuels. The three main types, bioethanol, biodiesel, and biogas, offer sustainable energy solutions by utilising existing combustion engines and fuel distribution infrastructure while significantly reducing net carbon emissions. Bioethanol is the most widely produced biofuel globally. Compared to gasoline, bioethanol can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 52% (U.S. Department of Energy, 2022). It plays a crucial role in enhancing energy security by decreasing dependence on imported oil and promoting circularity by converting agricultural residues into valuable energy, thereby supporting both waste management and rural economic development (El-Araby, 2024). Its compatibility with current transportation systems, especially through common blends like E10 and E85, makes bioethanol an immediately deployable and scalable tool for decarbonising the transport sector (Renewable Fuels Association, 2025). As the world transitions toward cleaner energy systems, biofuels, and particularly bioethanol, are poised to be integral to meeting both environmental and economic sustainability goals.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that biofuel demand is set to increase by 38 billion litres over 2023–2028 and could deliver 20% of the emissions reductions required in transport by 2030 under net-zero pathways (IEA, 2023). However, their scalability and sustainability depend on the choice of feedstock and production methods.

Production and Types

Bioethanol is a renewable liquid fuel that has emerged as a gasoline substitute or additive. Its production involves converting biomass into ethanol through microbial biochemical processes, primarily using fermentable sugars and starch derived from food sources like corn and sugarcane. The bioethanol production process typically involves several key steps: hydrolysis, fermentation, and product purification (Achinas & Euverink, 2016).

Bioethanol is typically classified into first- and second-generation based on feedstock type. While these remain the primary modes of production, third- and fourth-generation bioethanol technologies, which rely on advanced feedstocks such as algae or genetically engineered microorganisms, are still in the early stages of development but are increasingly gaining attention as potential future solutions for sustainable fuel production (Alalwan et al., 2019).

Food vs. Fuel and Land-use Change (LUC)

The widespread use of ‘first-generation’ feedstock sources for bioethanol production has raised concerns over food security and land-use change (Subramaniam et al., 2020). The global expansion of crop-based biofuels has demonstrated troubling interconnections between energy and food production systems, as first-generation bioethanol relies predominantly on food crops such as corn, sugarcane, and wheat, which could otherwise directly contribute to global food supplies. A 2016 paper indicates that biofuels rely on approximately 2-3% of global agricultural water and land resources, which could potentially feed about 30% of the malnourished population worldwide (Rulli et al., 2016). Another significant concern surrounding biofuels is the global policy landscape governing LUC, as research suggests that, under current regulatory conditions, the carbon dioxide emissions from biofuel production may actually surpass those from burning fossil diesel (Merfort et al., 2023). However, it is important to recognise that despite over a decade of research on LUC-related emissions, findings remain inconclusive and continue to be a subject of ongoing debate (Taheripour et al., 2024).

Second-Generation Bioethanol

In recent years, a significant focus has been on optimising bioethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass, particularly from agro-industrial wastes. Produced from lignocellulosic agricultural residues such as corn stover, rice straw, and sugarcane bagasse, second-generation bioethanol offers a sustainable pathway to decarbonise transport without the land-use change (LUC) and food-security impacts of its first-generation counterpart (IEA, 2008; Jeswani et al., 2020).

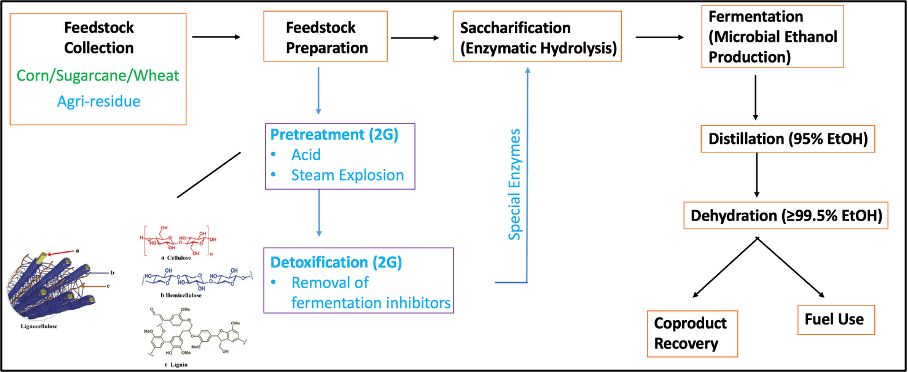

The production of 2G bioethanol shares several fundamental steps with 1G bioethanol (Figure 1); however, key differences arise in the initial stages of feedstock processing (Correia et al., 2024; Robak & Balcerek, 2018). Unlike 1G processes that use readily fermentable sugars from food crops, 2G bioethanol production begins with lignocellulosic biomass, which requires extensive pretreatment, such as steam explosion or acid hydrolysis, to break down the rigid structure composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (Gandam et al., 2022). This is followed by a detoxification step to remove fermentation inhibitors generated during pretreatment. Specialised enzymes are then employed to hydrolyse the complex carbohydrates into fermentable sugars (Vasić et al., 2021). These additional steps are both energy- and resource-intensive, significantly contributing to the higher production costs of 2G bioethanol (Iram et al., 2022).

Studies have demonstrated the feasibility and potential of converting agricultural residues, such as rice straw and corn stover, into 2G bioethanol through various biochemical processes (El-Araby, 2024; Rajeswari et al., 2022). The GHG-reduction potential of lignocellulosic biomass is substantial but variable based on feedstock source (Sharma et al., 2020). Global estimates suggest it could generate up to approximately 491 billion litres, or 16 times current global production levels (Saini et al., 2014).

Policy Overview

Biofuel development varies worldwide, shaped by national policies, resource availability, and market conditions like commodity prices. Government policies play a key role in promoting these technologies, often developed in collaboration with industry, researchers, and environmental groups. These frameworks aim to balance energy security, sustainability, and economic growth and must evolve with technological advances and changing environmental priorities.

Figure 2 shows the top bioethanol-producing regions globally. A large variation in production can be observed, ranging from 1.2 billion L/year to 61.4 billion L/year. The United States of America and Brazil lead the rest of the world by a huge margin, with 61.4 billion litres and 33.2 billion litres produced each year, respectively. Other countries such as India, the European Union, China, Canada, Thailand, and Argentina have production in the range of 1.2 billion to 6.2 billion litres per year. It cannot be missed that very few countries produce more than 1 billion litres/year, clearly indicating that the production of bioethanol at scale is limited. In contrast, the widespread production of bioethanol in the United States of America and Brazil is worth noting.

The large-scale production of bioethanol in the United States and Brazil can be attributed to a combination of abundant feedstock availability and long-standing, supportive policy frameworks. In the U.S., corn serves as the primary feedstock, while Brazil relies on sugarcane, both of which are rich in fermentable sugars, easy to process, and widely cultivated. These countries have also developed well-established and efficient supply chains to support consistent bioethanol production. Importantly, both nations have maintained a long-term policy commitment to integrating bioethanol into their transportation fuel mix, ensuring sustained demand and industry stability. Policy mechanisms supporting bioethanol development in these regions will be discussed in a separate section.

Brazil and the United States have strategically linked bioethanol use with efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in the transportation sector. Technological maturity in bioethanol production and the widespread compatibility of vehicles with ethanol-blended fuels have significantly contributed to its broader adoption. Globally, many countries have followed suit by introducing policy mandates for blending bioethanol with conventional fuels, thereby stimulating demand and supporting domestic production. While current bioethanol production remains largely dependent on first-generation feedstocks, there is a growing shift toward advanced biofuels derived from agricultural residues and organic waste, reflecting increased emphasis on sustainability and resource efficiency.

Policy Frameworks

With a total of 44 policies on bioethanol across the globe, most of them are very recent, belonging to only the past two decades (IEA Policy Database). Interestingly, one of the earliest policies on ethanol came from Guatemala in 1985, while not currently implemented properly, the policy came in response to rising fossil fuel prices and low sugar costs (Tomei & Diaz-Chavez, 2013). Table 1 summarises the primary national policy frameworks, key feedstocks used, and major 2G bioethanol projects in the United States, Brazil, India, the European Union, and China, the largest bioethanol producers globally.

| Country | Key Feedstock | Policy Drivers | Major Projects/Players |

| Brazil | Sugarcane bagasse (USDA, 2024) | RenovaBio CBIO credits (USDA, 2024) | Raízen (Bonfim, Costa Pinto) (USDA, 2024) |

| United States | Corn stover (Ethanol Producer Magazine, 2015) | RFS mandates, 45Z Tax Credit (US DoT & IRS, 2025) | DuPont (Nevada)* (McCoy, 2023) *shut down in 2017 due to high operational costs |

| India | Rice straw (Mookherjee, 2024) | JI-VAN Yojana, E20 target (MPNG, Government of India, 2024) | Indian Oil Corporation Limited Panipat Biorefinery (Mookherjee, 2024) |

| European Union | Agricultural waste (European Commission, 2015) | RED II Directive (European Commission, n.d.) | Cepsa-Bio-Oils plant (To be completed in 2026) (Cepsa, 2024) |

| China | Corn stover (IEA Bioenergy, 2016) | 13th/14th Five-Year Plans (USDA FAS, 2024) | Clariant plant (Clariant Ltd., 2022) |

It is important to note that reliable data on 2G bioethanol production remains limited, making it difficult to accurately assess production capacities across these regions. The key policy frameworks and incentives for 2G bioethanol production in the regions mentioned earlier are highlighted in Table 2.

| Region | Key Policy Frameworks | Incentives |

| Brazil | Recent initiatives encourage the development of 2G ethanol from agricultural residues.: RenovaBio, Ordinance #75/2015 for mandatory blending. (IEA, 2024; USDA, 2024) | Offers tax incentives (RenovaBio) and has established a decarbonization credit (CBIO: equivalent to 1 ton of CO2 avoided) market to promote biofuels. RenovaBio: Incentives for producing bioethanol (including 2G through decarbonisation credits: CBIOs) |

| United States | Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) mandates specific volumes of renewable fuels, including advanced biofuels like 2G ethanol, to be blended into transportation fuels. (Clean Air Task Force, 2023) | Provides financial incentives, grants, and loan guarantees for 2G biofuel projects. (US Department of Energy, 2013) 45Z Tax Credits: per gallon based on the fuel’s carbon intensity (Renewable Fuels Association, 2024) |

| India | The National Policy on Biofuels (2022 Amendment) advances the ethanol blending target to 20% by 2025-26, emphasizing the use of non-food feedstocks and waste materials for 2G ethanol production. (IEA, 2023; USDA FAS, 2023) | Launched the PM JI-VAN Yojana, offering viability gap funding to establish 2G ethanol biorefineries. (MPNG, Government of India, 2024b) Research funding provided under BioE3 (Biotechnology for Economy, Environment, and Employment) Policy (The Hindu & Koshy, 2024) |

| European Union | The Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) sets binding targets for renewable energy in transport, capping first-generation biofuels (LUC, food) and promoting advanced biofuels. (European Commission, n.d.) | Implements sustainability criteria and provides funding for research and development in advanced biofuels. (European Court of Auditors, 2023) |

| China | Focus shifting towards non-grain feedstocks to avoid food security issues. (IEA Bioenergy, 2016) | Provides subsidies and tax exemptions to bioethanol producers, especially those utilizing non-grain feedstocks. (USDA FAS, 2017) |

Policy support and incentives towards 2G bioethanol production have several socioeconomic and environmental benefits. The utilisation of agri-residue, which would otherwise have been burnt or disposed of improperly, helps develop circularity in agri-food systems. Developing supply chains for creating forward linkages of agri-residue from farms to biorefineries would generate new employment opportunities in the agriculture sector, thereby positively contributing to the rural economy. A full realisation of such a circular bioeconomic model will go a long way in supporting rural development while providing a pathway to decarbonisation.

Barriers to the Adoption of 2G Bioethanol

Supply Logistics

Agricultural residues are generated only at harvest, leading to pronounced seasonal peaks and off‑season shortages. Without dedicated infrastructure for harvesting, storage, and transport, biorefineries face feedstock shortages that force intermittent operation or reliance on spot markets at higher cost (IEA Bioenergy, 2022). Low bulk density further increases transportation costs and complexity of supply chain logistics, as residues occupy large volumes per ton delivered (Balan, 2014). Therefore, ensuring a stable and consistent feedstock supply requires innovative business models and investment in supply chain logistics, aggregation centres with covered storage facilities and coordinated collection networks.

Feedstock Variability

Feedstock type and homogeneity influence bioprocesses significantly at the industrial scale, influencing the choice of pretreatment methods, enzymes, and microbial strains for fermentation. As shown by Sharma et al. (2020), the GHG-reduction potential also varies by the choice of biomass used as feedstock.

Energy-Intensive Pretreatment

The pretreatment process requires the input of large amounts of heat and pressure, thereby increasing the energy consumption of the process, while also influencing operating costs and emissions (Ayodele et al., 2019; Sarkar et al., 2024).

Enzyme Cost and Efficiency

Specialist enzymes such as cellulases and hemicellulases, required at the hydrolysis step, are expensive to obtain and comprise close to 25% of the complete 2G bioethanol production process (Pattnaik et al., 2024). Feedstock variability may also influence enzymatic activity, thereby having greater process implications, hampering process consistency and scale-up. Improving enzymatic activity, stability, and recyclability is essential to reduce cost and enhance yield.

High Resource Consumption

The production process demands substantial water inputs. While there are not many studies addressing freshwater consumption, Gonzalez-Contreras et al. (2020) showed water consumption rates between 10-25 litres of water per litre of 2G ethanol produced. Mishra et al. (2018) estimated the total energy consumption of the process to be close to 8.3 MJ/kg of wheat straw feedstock used. More conclusive research is required to accurately evaluate the cost and resource requirements of 2G bioethanol production processes.

Complex Waste Streams

Pretreatment sometimes requires the use of acids and generates inhibitory by‑products such as furfurals that impede fermentation and require additional detoxification steps, adding cost and complexity (Balan, 2014).

Lack of Cost Competitiveness

The complexity of the production process makes 2G ethanol more expensive to produce in the short term, compared to its 1G counterpart (Junqueira et al., 2017). As previously mentioned, this has been one of the greatest challenges in 2G bioethanol gaining traction in countries like Brazil and the US. Policy mechanisms must favour the production of 2G ethanol through carbon credits, blending mandates, and offtake guarantees to incentivise investment in 2G technologies.

Policy Recommendations

Leverage Voluntary Carbon Markets

Integrating 2G bioethanol into voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) can mobilise significant private capital by converting avoided emissions into tradable credits. Farmers selling their agricultural residue to production facilities can also gain carbon credits, which can then be sold in carbon markets. To facilitate this, governments should develop standardised methodologies for quantifying lifecycle emissions reductions from 2G bioethanol and streamline verification under recognised VCM standards (such as Verra and Gold Standard). This also has the potential to incentivise stopping wasteful and environmentally harmful practices such as stubble burning at the end of the harvest cycle. Integration of agriresidue supply into VCMs also allows smallholder farmers an additional revenue stream, incentivising sustainable agricultural practices.

Establish Floor‑Price Mechanisms

Price uncertainty in nascent 2G markets deters investment in 2G bioethanol projects. Introducing a minimum support price for 2G ethanol offtake, analogous to feed-in tariffs in renewables, would guarantee a floor revenue per litre until plants reach commercial break-even. Such a mechanism could be structured as a “buyer of last resort” contract, with government or mandated blending entities covering the gap between market and floor prices. A time-bound floor price (for example, 5-7 years) encourages cost‑reduction without indefinite subsidies.

Phase-wise Substitution Targets

Time-bound blending mandates for replacing 1G with 2G bioethanol create predictable demand signals. For example, the EU’s RED II sets sub-targets for advanced biofuels rising from 0.2% in 2022 to 3.5% by 2030 under a 14% transport renewables mandate (European Commission, n.d.). Similarly, India’s E20 roadmap (20% ethanol by 2025‑26) could specify that at least 5% be from 2G sources, ramping to 15% by 2030. This graduated approach provides a structured and certain roadmap for deploying 2G bioethanol.

Enhance R&D Support

Reducing the high costs of pretreatment, enzymes, and water use is crucial to make 2G production processes more cost-effective. Public R&D funding must prioritise the development of next-gen pretreatment technologies, enzyme and microbial engineering to enhance process efficiency, and process circularity to reduce water and energy losses. One prominent example is India’s BioE3 policy. It aims to foster high-performance biomanufacturing, leveraging biotechnology for economic development, environmental sustainability, and job creation, incentivising large-scale funding into the 2G bioethanol research and development.

Strengthen Supply‑Chain Infrastructure

Ensuring year-round feedstock delivery requires dedicated logistics policies. These may include the creation of government-funded or subsidised collection facilities to collect and transport agricultural residue to aggregation hubs. It is important to plan the setup of 2G bioethanol facilities near farming regions to bale and preprocess the agriresidues.

To incentivise the use of agricultural residues for 2G bioethanol production, the state of Haryana, India, provides financial support to farmers, including ₹1000 per acre for crop residue baling and an additional ₹500/MT in areas identified by IOCL for feedstock supply to its Panipat biorefinery. This collaborative model between government and industry exemplifies how targeted incentives can mobilise farmer participation and stabilise feedstock supply chains.

Promote Public Awareness and Adoption

Promoting public awareness and adoption of 2G bioethanol is crucial to accelerating its integration into national energy systems. Launching targeted awareness campaigns can help highlight the sustainability and climate advantages of 2G bioethanol, such as its significantly lower lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions and ability to utilise agricultural residues that would otherwise be burned or wasted. These campaigns can encourage investment from stakeholders across the value chain by showcasing the environmental and socio-economic benefits, including rural job creation, reduced air pollution, and enhanced energy security. Effective outreach should be conducted through partnerships with farmer organisations, civil society groups, industry stakeholders, and media outlets to build trust, dispel myths, and support informed decision-making among consumers, producers, and policymakers.

Future Work

To fully realise the decarbonisation potential of agri-residue-derived bioethanol, it is imperative to have reliable and granular data on 2G bioethanol production capacities by region, type of feedstock used, and the quantities available thereof, and plant performance metrics such as energy and resource use per litre of bioethanol produced. Such publicly available data would enable more informed development of better national and international policies. The rapid adoption of 2G bioethanol requires strengthening supply chains for feedstock, with particular attention to farmer readiness, seasonal availability, techno-economic viability and logistics. A long-term policy framework must be developed to make 2G bioethanol production and deployment more economically viable in comparison to 1G bioethanol production. Further research and development need to be undertaken to increase the process efficiency of 2G bioethanol production. This comprehensive approach will facilitate the development of 2G bioethanol as a globally viable, sustainable alternative fuel for the transport sector, offering significantly lower greenhouse gas emissions compared to conventional fossil fuels.

References:

Achinas, S., & Euverink, G. J. W. (2016). Consolidated briefing of biochemical ethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology, 23, 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejbt.2016.07.006

Alalwan, H. A., Alminshid, A. H., & Aljaafari, H. A. (2019). Promising evolution of biofuel generations. Subject review. Renewable Energy Focus, 28, 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ref.2018.12.006

Ayodele, B. V., Alsaffar, M. A., & Mustapa, S. I. (2019). An overview of integration opportunities for sustainable bioethanol production from first- and second-generation sugar-based feedstocks. Journal of Cleaner Production, 245, 118857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118857

Balan, V. (2014). Current Challenges in Commercially Producing Biofuels from Lignocellulosic Biomass. ISRN Biotechnology, 2014, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/463074

Cellulosic feedstocks of the future | Ethanol Producer Magazine. (2015, September 12). https://ethanolproducer.com/articles/cellulosic-feedstocks-of-the-future-12597

Cepsa. (2024, February 20). CEPSA and Bio-Oils begin construction on the largest 2G biofuels plant in southern Europe with investment of 1.2 billion euros. CEPSA.com. https://www.moeveglobal.com/en/press/cepsa-and-bio-oils-build-the-largest-2g-biofuel-plant

Clariant Ltd. (2022, June 9). Clariant and Harbin Hulan Sino-Dan Jianye Bio-Energy announce license agreement for sunliquid® cellulosic ethanol technology in China. https://www.clariant.com/en/Corporate/News/2021/02/Clariant-and-Harbin-Hulan-SinoDan-Jianye-BioEnergy-announce-license-agreement-for-sunliquid-cellulos

Clean Air Task Force. (2023, August 11). U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard: Challenges and opportunities on the path to decarbonizing the transportation sector. https://www.catf.us/2023/06/us-renewable-fuel-standard-challenges-opportunities-path-decarbonizing-transportation-sector/

Correia, B., Matos, H. A., Lopes, T. F., Marques, S., & Gírio, F. (2024). Sustainability Assessment of 2G Bioethanol Production from Residual Lignocellulosic Biomass. Processes, 12(5), 987. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12050987

CSIRO. (2024). Global Carbon Budget. https://www.csiro.au/en/research/environmental-impacts/emissions/Global-greenhouse-gas-budgets/Global-carbon-budget#:~:text=Fossil%20fuel%20CO2%20includes,2%20emissions%20from%20human%20activities.

Department of the Treasury & Internal Revenue Service. (2025). Section 45Z Clean Fuel Production Credit; Request for public comments. In Department of the Treasury (Notice 2025-10). https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-25-10.pdf#page=2.16

El-Araby, R. (2024). Biofuel production: exploring renewable energy solutions for a greener future. Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-024-02571-9

European Commission. (2015, May 5). Second Generation BIoethanol sustainable production based on Organosolv Process at atmospherIc Conditions. CORDIS | European Commission. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/657867

European Commission. (n.d.). Renewable Energy – Recast to 2030 (RED II). The Joint Research Centre: EU Science Hub. https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/welcome-jec-website/reference-regulatory-framework/renewable-energy-recast-2030-red-ii_en

EUROPEAN COURT OF AUDITORS. (2023, December 13). Special Report 29/2023: The EU’s support for sustainable biofuels in transport. European Court of Auditors. https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/publications?ref=SR-2023-29

Gandam, P. K., Chinta, M. L., Pabbathi, N. P. P., Baadhe, R. R., Sharma, M., Thakur, V. K., Sharma, G. D., Ranjitha, J., & Gupta, V. K. (2022). Second-generation bioethanol production from corncob – A comprehensive review on pretreatment and bioconversion strategies, including techno-economic and lifecycle perspective. Industrial Crops and Products, 186, 115245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115245

Gonzalez-Contreras, M., Lugo-Mendez, H., Sales-Cruz, M., & Lopez-Arenas, T. (2020). Intensification of the 2G bioethanol production process. DOAJ (DOAJ: Directory of Open Access Journals). https://doi.org/10.3303/cet2079021

Hannah Ritchie (2020) - “Cars, planes, trains: where do CO₂ emissions from transport come from?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions-from-transport' [Online Resource]

IEA (2008), From 1st- to 2nd-Generation Biofuel Technologies, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/from-1st-to-2nd-generation-biofuel-technologies, Licence: CC BY 4.0

IEA (2024), CO2 Emissions in 2023, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2023, Licence: CC BY 4.0

IEA Bioenergy. (2016). The potential of biofuels in China. https://www.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/The-Potential-of-biofuels-in-China-IEA-Bioenergy-Task-39-September-2016.pdf

IEA Bioenergy. (2022). Feedstock to Biofuels: Opportunities for Advanced biofuels - Supply chain analysis and reduction in CAPEX/OPEX. In IEA Bioenergy: Task 39 (Task 39). https://task39.ieabioenergy.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/37/2023/01/The-Feedstock-to-Biofuels-Opportunities-for-advanced-biofuels.pdf

IEA. (2023, February 1). National Policy on Biofuels (2022 Amendment) – Policies. IEA. https://www.iea.org/policies/17006-national-policy-on-biofuels-2022-amendment

IEA. (2024, July 9). Ordinance No 75/2015 on Ethanol Blending Mandate – Policies - IEA. IEA. https://www.iea.org/policies/2021-ordinance-no-752015-on-ethanol-blending-mandate

IPCC. (2018). Chapter 2 — Global Warming of 1.5 oC. Ipcc.ch; Global Warming of 1.5 oC. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/chapter-2/?

Iram, A., Cekmecelioglu, D., & Demirci, A. (2022). Integrating 1G with 2G Bioethanol Production by Using Distillers’ Dried Grains with Solubles (DDGS) as the Feedstock for Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Production. Fermentation, 8(12), 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation8120705

Jeswani, H. K., Chilvers, A., & Azapagic, A. (2020). Environmental sustainability of biofuels: a review. Proceedings of the Royal Society a Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences, 476(2243). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2020.0351

Junqueira, T. L., Chagas, M. F., Gouveia, V. L. R., Rezende, M. C. a. F., Watanabe, M. D. B., Jesus, C. D. F., Cavalett, O., Milanez, A. Y., & Bonomi, A. (2017). Techno-economic analysis and climate change impacts of sugarcane biorefineries considering different time horizons. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-017-0722-3

McCoy, M. (2023, March 25). Former DuPont ethanol plant is making methane. Chemical & Engineering News. https://cen.acs.org/energy/biofuels/Former-DuPont-ethanol-plant-reborn/100/i18

Merfort, L., Bauer, N., Humpenöder, F., Klein, D., Strefler, J., Popp, A., Luderer, G., & Kriegler, E. (2023). State of global land regulation inadequate to control biofuel land-use-change emissions. Nature Climate Change, 13(7), 610–612. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01711-7

Mishra, A., Kumar, A., & Ghosh, S. (2018). Energy assessment of second generation (2G) ethanol production from wheat straw in Indian scenario. 3 Biotech, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-018-1135-0

Mookherjee, P. (2024, August 20). Addressing feedstock challenges to unlock India’s biofuel potential. orfonline.org. https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/addressing-feedstock-challenges-to-unlock-india-s-biofuel-potential

MPNG, Government of India. (2024). Refinery Division - Second generation (2G) Ethanol | Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas | Government of India. https://mopng.gov.in/en/refining/second-generation-ethenol

MPNG, Government of India. (2024b, August 9). Cabinet approves amendment in “Pradhan Mantri JI-VAN Yojana” for providing financial support to advanced biofuel projects using lignocellulosic biomass and other renewable feedstock. pib.gov.in. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=2043926

Patel, K., & Singh, S. (2024). Environmental sustainability, energy efficiency and uncertainty analysis of agricultural residue-based bioethanol production: A comprehensive life cycle assessment study. Biomass and Bioenergy, 191, 107439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2024.107439

Pattnaik, F., Patra, B. R., Nanda, S., Mohanty, M. K., Dalai, A. K., & Rawat, J. (2024). Drivers and barriers in the production and utilization of Second-Generation bioethanol in India. Recycling, 9(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling9010019

Rajeswari, S., Baskaran, D., Saravanan, P., Rajasimman, M., Rajamohan, N., & Vasseghian, Y. (2022). Production of ethanol from biomass – Recent research, scientometric review and future perspectives. Fuel, 317, 123448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123448

Renewable Fuels Association. (2024, November 8). RFA welcomes legislation extending Second-Generation Biofuels tax Credit. https://ethanolrfa.org/media-and-news/category/news-releases/article/2024/11/rfa-welcomes-legislation-extending-second-generation-biofuels-tax-credit

Renewable Fuels Association. (2024). Annual Ethanol Production | Renewable Fuels Association. https://ethanolrfa.org/markets-and-statistics/annual-ethanol-production

Robak, K., & Balcerek, M. (2018). Review of Second-Generation Bioethanol Production from Residual Biomass. Food Technology and Biotechnology, 56(2). https://doi.org/10.17113/ftb.56.02.18.5428

Rulli, M. C., Bellomi, D., Cazzoli, A., De Carolis, G., & D’Odorico, P. (2016). The water-land-food nexus of first-generation biofuels. Scientific Reports, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22521

Saini, J. K., Saini, R., & Tewari, L. (2014). Lignocellulosic agriculture wastes as biomass feedstocks for second-generation bioethanol production: concepts and recent developments. 3 Biotech, 5(4), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-014-0246-5

Sarkar, D., Patil, P. B., Poddar, K., & Sarkar, A. (2024). Boosting 2G bioethanol production by overexpressing dehydrogenase genes in Klebsiella sp. SWET4 : ANN optimization, scale-up, and economic sustainability. Renewable Energy, 122093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.122093

Sharma, B., Larroche, C., & Dussap, C. (2020). Comprehensive assessment of 2G bioethanol production. Bioresource Technology, 313, 123630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123630

Subramaniam, Y., Masron, T. A., & Azman, N. H. N. (2020). Biofuels, environmental sustainability, and food security: A review of 51 countries. Energy Research & Social Science, 68, 101549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101549

Taheripour, F., Mueller, S., Emery, I., Karami, O., Sajedinia, E., Zhuang, Q., & Wang, M. (2024). Biofuels Induced land use change Emissions: The role of Implemented Land use emission factors. Sustainability, 16(7), 2729. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072729

The Hindu, & Koshy, J. (2024, August 24). Cabinet approves scheme to boost biotech manufacturing. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/cabinet-nod-to-bioe3-policy-for-innovation-driven-support-to-research-and-development/article68562996.ece

Tomei, J., & Diaz-Chavez, R. (2013). Guatemala. In Springer eBooks (pp. 179–201). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9275-7_8

UNFCCC. (n.d.). The Paris Agreement. United Nations Climate Change; United Nations. Retrieved April 22, 2025, from https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement

United States Department of Agriculture. (2024). Biofuels Annual. In fas.usda.gov (No. BR2024-0022). USDA. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Biofuels%20Annual_Brasilia_Brazil_BR2024-0022.pdf

US Department of Energy. (2013, January 2). Advanced biofuel production grants and loan guarantees. https://afdc.energy.gov/laws/8502#:~:text=The%20U.S.%20Department%20of%20Agriculture,scale%20biorefineries%20are%20also%20available.

US DOE. (2022, June 23). Ethanol vs. Petroleum-Based Fuel Carbon Emissions. Energy.gov. Retrieved April 8, 2025, from https://www.energy.gov/eere/bioenergy/articles/ethanol-vs-petroleum-based-fuel-carbon-emissions

USDA FAS. (2017). Biofuels Annual - China. In fas.usda.gov (No. CH16067). https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Biofuels%20Annual_Beijing_China%20-%20Peoples%20Republic%20of_1-18-2017.pdf

USDA FAS. (2023). Biofuels Annual - 2023. In fas.usda.gov (No. IN2023-0039). USDA. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Biofuels%20Annual_New%20Delhi_India_IN2023-0039.pdf

USDA FAS. (2024). Biofuels Annual. In https://fas.usda.gov (No. CH2024-0100). US Department of Agriculture. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Biofuels+Annual_Beijing_China+-+People%27s+Republic+of_CH2024-0100.pdf#page=28.09

Van Gogh, M., Sandström, J., & World Economic Forum. (2024, April 28). Why a multi-fuel infrastructure network is key to transport and heavy industry’s energy transition. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/04/multi-fuel-infrastructure-network-transport-heavy-industry-energy-transition/

Vasić, K., Knez, Ž., & Leitgeb, M. (2021). Bioethanol Production by Enzymatic Hydrolysis from Different Lignocellulosic Sources. Molecules, 26(3), 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26030753

Leave a comment